Editor’s Note: This article is part of a series that Rethinking65 is doing on viewpoints of industry leaders who attended the Schwab Impact 2023 conference.

Worries about market volatility and inflation keep many new and soon-to-be retirees awake at night. But a lack of knowledge and misconceptions about sequence-of-return risk — the impact that the timing of withdrawals could have on retirement portfolios during bad markets — may be unnecessarily adding to the angst.

Many people say “it would be terrible to have a bear market the day after you retire. Actually, it turns out that has basically no impact on your retirement,” Michael Kitces, head of planning strategies at Buckingham Wealth Partners, said in late October during a breakout session on sequence-of-return risk at the Schwab Impact 2023 conference.

For example, if you looked at the portfolio of someone who retired in 1987, you wouldn’t know Black Monday had occurred because the stock market recovered quickly and strongly, he said. But a bear market followed by a slow recovery or extended period of low returns during a client’s first decade of retirement could be detrimental.

“Sequence-of-return risk is not a story of the bad first year in the markets; It’s the story of the bad decade,” said Kitces, also publisher of Nerd’s Eye View, a financial planning industry blog on Kitces.com.

Sequence of return is not a new phenomenon, but Kitces continues to discuss it passionately with advisors. Even now, “many have heard the label but not really how it actually works, where sequence of return comes from, and what causes it and doesn’t cause it,” he said.

Tweaking the buckets

As advisors, “we’re usually trying to answer one or two fairly fundamental client questions when we’re dealing with all these retirement issues,” said Kitces. Some clients say, ‘I’ve got all these different dollars I’ve been building up during my accumulation years – I’ve got money in IRAs, 401(k)s, real estate …. I don’t really want to work anymore. I’m trying to figure out how do I turn buckets of money into checks that come into my bank account on an ongoing basis for the rest of my retirement?’”

Other clients have figured out where and how they want to live in retirement and have done some rough calculations. Their big question is, “How much money do I need in the buckets to make that vision happen?” said Kitces, and they want to know how much they can safely spend without having to worry about the markets.

No matter where clients stand, “we have to create some kind of translation from assets to sustainable cash flows that can occur for a multi-decade period,” he said. And factoring in sequence-of-return risk is important.

Number crunching

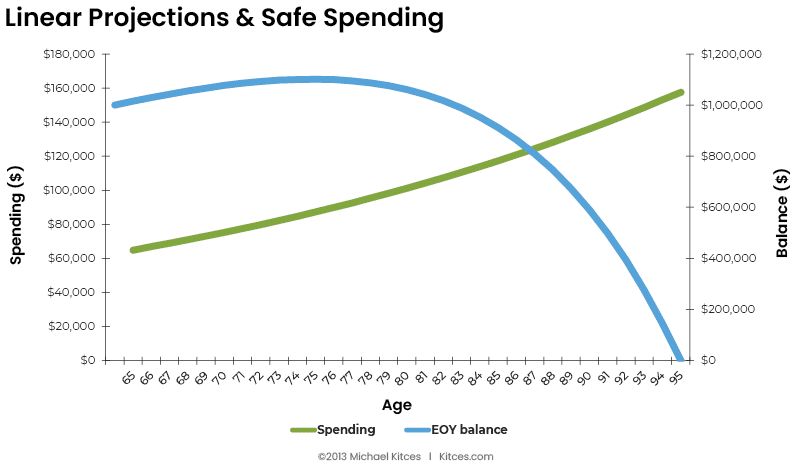

During the session, Kitces shared an example of a 65-year-old retiree planning for a 30-year retirement facing 3% annual inflation. The client’s initial portfolio of $1 million — 60% stocks/40% bonds — would be rebalanced annually. He also assumed stock returns of 10% (7% real return after inflation), bond returns of 5% (2% real) and an average portfolio return of 8% (5% real). Using these linear projections, the retiree could safely make annual withdrawals of nearly $66,000 (roughly 6.6%) from their retirement portfolio, said Kitces.

This is significantly higher than retired financial planner William Bengen’s 4% rule, [and higher than Bengen’s recent revisions]. Even so, the client’s spending and end-of-year balance won’t intersect until age 87 and the client won’t run out of assets until 97, said Kitces.

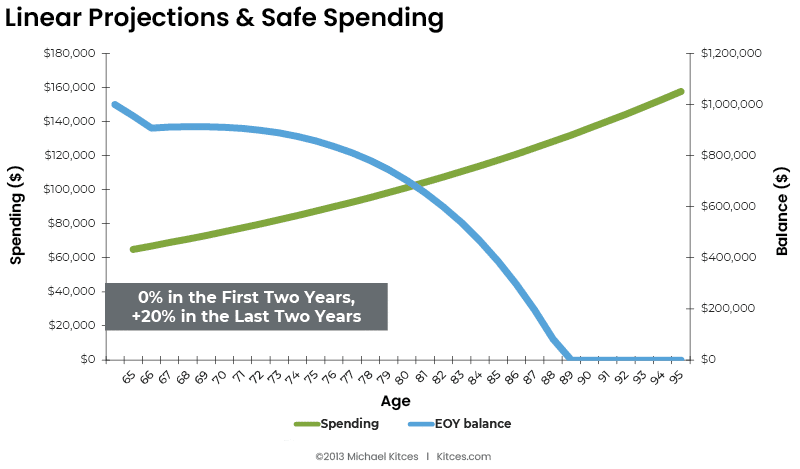

Now let’s assume instead that stock returns are 0% during the first two years of retirement and 20% during the last two years of the retiree’s life. Although this still translates into average annual gains of 10%, the retiree’s spending and end-of-year balance will now intersect at age 82 and she’ll run out of money at around 89, said Kitces.

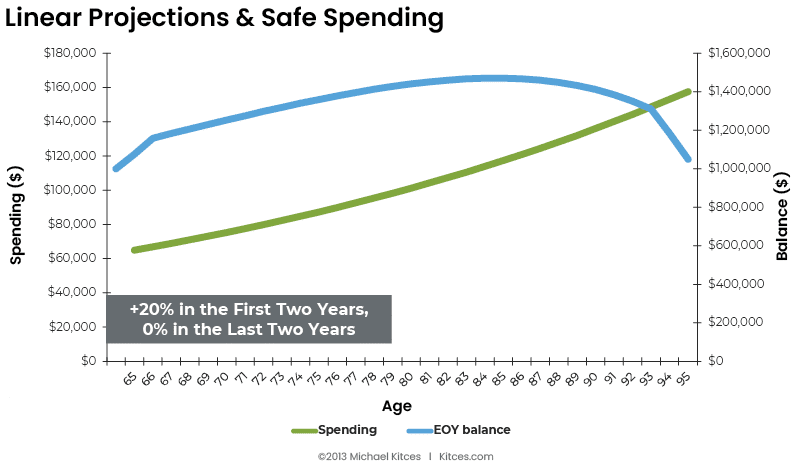

Reversing things, the client would fare much better if stocks gain 20% during her first two years of retirement and 0% in her last two years. Her spending won’t exceed her end-of-year balance until she is about 93 and she’ll still have about $1 million in her retirement portfolio at 95.

More factors, more math

And don’t forget about inflation, Kitces also cautioned. “Plus or minus a half a percent of inflation is a nine-year swing on the survival rate of a 30-year portfolio,” he said. “Anybody have a highly competent projection on inflation within less than half a percent?” In addition, “With the compounding effects it gets really dramatic.”

Kitces didn’t just share hypothetical numbers but also did a time warp back to the 30-year period of 1969 to 1999. Over this period, the real rates of return — after backing out 5.3% inflation — were 8.1% on stocks (with a long term average closer to 7%) and 3.3% for bonds.

“This was an absolutely amazing time to be an investor. If all you did was buy a 60/40 portfolio and annually rebalanced it, you got 11 ½% for 30 years,” he said. “If you put that into your planning software today, you’d probably get sued!” But you’d also determine that investor could withdraw 7.4% a year on their $1 million portfolio.

Inflation pain

However, “5.3% inflation is pretty brutal,” Kitces added. “It means the car at the end cost as much as the house at the beginning. That’s about how it plays out.” So that “$74,000 lifestyle grows to almost $350,000 a year at the end just to maintain the same $74,000 lifestyle.”

Let’s assume “you actually take that advice and you retire in 1969 spending $74,000 a year … You’re flat broke in 12 years,” he said. “You make it in 30, but the problem is 1969 was actually a down year in the markets, so you dig a hole for yourself almost immediately. You spend three years recovering getting back to where you started. Then the 73-74 bear market hits. By now, your withdrawal rate has gone from 7[%] to almost 15% on a smaller account balance. And then you basically just spent six more years finishing going broke while the market is trying to recover, but you don’t have nearly enough to sustain growth plus the withdrawals that you’re taking at this point.”

Really bad timing

“The timing is particularly ironic,” Kitces continued. The 1969 retiree goes broke 12 years, in 1981, which, for the markets “was finally the bottom of all the pain,” he said. “You actually get almost 14% on a balanced portfolio for the last 18 years” leading up to 1999. “Except you’re getting 14% returns on capital zero, which means it doesn’t really help.”

Kitces shared more history, with data going all the way back to the 1870s.

“The key thing to understand is that the safe-withdrawal-rate research was not built on what is safe to withdraw with the average returns in history. It was built around, ‘What’s the safe thing to withdraw with the worst sequence we’ve ever seen in history?’ which was what happens if you retired in 1966 and the stock market gained not $1 appreciation for 15 years,” he said.

Two sides and strategies

“Sequence-of-return risk cuts both ways,” said Kitces. “When you get the bad sequences, you quickly dig a hole so deep you can’t recover from it. But when you get a good sequence, you can last so far ahead that the worst decade of a century to be a retiree is basically just a speed bump.”

“If the first decade [of retirement] is good enough, you can’t put a dent in the original plan,” he said. “And if the first decade is really bad and you are not doing something to defend against a bad decade, whatever you’re doing in the short term slowly grinds out.”

Managing sequence-of-return risk can be done through safe withdrawal rates, dynamic asset allocation and dynamic spending strategies, said Kitces. Withdrawal rates can be tweaked to factor in taxes, time horizons, legacy, diversification, risk tolerance and more.

Dynamic asset allocation employs traditional buckets (stocks, bonds and cash) as well as annuity buckets. For example, Social Security and immediate annuities can be used for essential expenses while portfolio withdrawals are reserved for discretionary expenses. Dynamic asset allocation also looks at rising equity glidepaths and valuation-based asset allocation. We’ll get to dynamic spending strategies in a bit.

Among other approaches, Kitces also likes to use what he calls a “bond tent strategy,” building up an extra allocation of bonds and fixed income for clients early in retirement. “It’s like a little tent we’re going to hide in for the first 10 years, and then we’re going to spend the tent down.”

Monkeys and bumper lanes

As a rule of thumb, “when returns are bad in the first half of retirement, the safe withdrawal rate is bad for all retirement, and when returns are good in the first half of retirement, the safe withdrawal rate is better for all of retirement,” said Kitces. “Roughly the 10- to 15-year time period really is the sweet spot that is most predictive.”

In contrast, “One-year returns have basically no prediction on 30-year withdrawals,” he said. “If you chart it, it’s like monkeys throwing darts – just like a random pattern of darts.”

As important as it is to make sure clients don’t run out of money, advisors also need to think about their clients’ goals – such as enjoying some of their wealth and not just saving it for their kids, said Kitces. That’s where dynamic spending strategies come in.

One of these strategies is what he calls “ratcheting.” He tells clients that they’ll start at a baseline safe-withdrawal rate, such as 4% or 5% and that “if we start getting a good sequence and we’re far enough ahead, we’ll give you a raise,” he said. “We don’t just wait till the end to find out you had too much.”

Another dynamic spending strategy he uses is upper and lower guardrails, which he likened to bumper lanes at bowling alleys. “If your portfolio is growing and you hit the bumpers, you get more,” he said he tells clients. And if their portfolio drops relative to their spending and they hit an upper bumper, he adjusts withdrawals rates downward.

“I don’t know which properties you’re going to hit,” he tells clients. “We’ll see what the markets do, but I know you’re going to make it to the end because I’m keeping you in a reasonably safe zone.”

Advisors can mix and match the strategies they use to keep clients safe, he said, noting that he personally likes buckets. And just as advisors use investment policy statements, he’s also seeing more develop withdrawal policy statements that explain their liquidation strategy and the triggers.

Jerilyn Klein is editorial director of Rethinking65