In Part 1 of this two-part article for Rethinking65, I mentioned that there is no easy answer when clients ask, “What is a good return on my rental property?” It’s important to reframe this question so the discussion is more meaningful, which leads to a lot of good coaching opportunities for advisors.

In this article, we are going to look at yearly income, which produces the yield or annual rate of return.

Let’s assume the yield on a client’s rental property is 4.5%. Here’s a closer look at how to evaluate yield on rental properties.

The “When 4.5% Equals 6.9%” Investor

Let’s add tax benefits to this discussion. In summary, here is how a real estate tax shelter works:

- If the rental carries debt, the owner can write off mortgage interest against the income from that rental. The interest deduction is not capped, unlike the deduction for interest on a primary home mortgage.

- The owner can also take straight-line depreciation of the value of the improved property. Land does not count because it does not depreciate.

Let’s look at a hypothetical rental investment that produces a first-year yield of 4.5%:

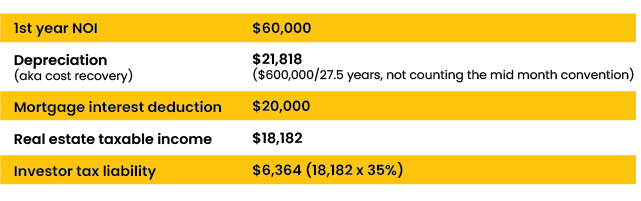

The calculation of first-year tax savings is below:

The deductions reduced taxable income from $60,000 to $18,182. For anyone in a higher marginal tax bracket, this tax shelter is significant. This also means that when comparing this to a fully taxable investment, the 4.5% yield needs to be adjusted to account for its tax efficiency. A tax-equivalent yield is the yield divided by 1 minus an investor’s income tax bracket. In this case, that means .045/(1-.35) or .65, which equals 6.9%.

Again, this is math that most investors or advisors do not consider. Before concluding this scenario, let’s do a little clean-up for those seeking fine print.

- Forget for a moment that this example does not resemble your rental property, your local market values, rents, improved property percentage, etc. This is a concept that will play out similarly to directly held rental investments around the country (the biggest variable is state taxes.)

- Depreciation taken during the life of the investment is recaptured at 25% upon disposition of the asset. Some investors use Section 1031 exchanges until they die (which defers and eventually eliminates recapture and capital gains taxes because investment value steps up upon death). Other investors create trust strategies to eliminate recapture and capital gains taxes forever. Still, most will ultimately pay the recapture. At 25%, it is still a bargain. Suppose an advisor wanted to exact the impact of recapture. They could assume a modified recapture percentage that would factor in the 25%, discounted by the future value over a given period. This difference is nominal compared to the overall value of the deductions

- This calculation does not account for other factors like qualified business income (QBI) since not all investors will qualify for it.

- Real estate purchased in a self-directed retirement account does not benefit from the tax shelter, so we assume the investment is made with after-tax money.

- The calculation and results are different for real estate held in irrevocable trusts and other infrequently used entities.

- Most taxable investments are not taxed at the marginal tax rate. The tax-equivalent calculation allows advisors to compare this investment to the gross yield of others.

- You or a professional tax advisor should create an actual cash-flow and tax model for your client’s circumstances.

The bottom line on the tax-equivalent scenario is, 6.9% becomes a serious contributor to a retirement income strategy. All expenses are baked into the NOI used to calculate yield, so 6.9% is also net of advisor and account fees. Thanks to tax law, 6.9% becomes the new 4.5%, and real estate could earn a seat at the retirement income table. The main point behind this scenario is, when measuring property performance and contribution to overall financial goals, advisors should encourage clients to focus on after-tax performance.

The “Risk-Adjusted Rate of Return” Investor

The risk-adjusted rate of return is a staple in investment planning. But it is a financial concept that few real estate investors, few real estate brokers and few financial advisors consider. Before jumping too far ahead, a risk-adjusted rate of return is a modifier that puts returns into context based on the amount of risk involved in an investment. The higher the risk of an investment, the higher return an investor should seek for taking on that additional risk.

“The truth is, real estate is fraught with various threats that mostly show up in performance.”

Real estate-centered investors view real estate as rock-solid; It does not disappear. As proof, you can touch it. Grandparents have prospered from it. We live in it, so we have experience with it. These absolute affirmations assume no other risks in owning real estate. The truth is, real estate is fraught with various threats that mostly show up in performance. What follows are a few examples:

- Management risk. Many clients choose to manage their property directly. This preference sets the stage for the most significant threat they face. Most investors are not wired to be a landlord — collecting and increasing rents, handling emotional tenants, screening new tenants, setting rents correctly, etc. What compounds this risk is that the property is likely the most concentrated and most significant investment of equity they own. Of all the investment real estate service providers, I most admire good property managers, who for a fee can reduce management risk.

- Economic base risk. This is entirely out of the investor’s control. One of the extreme examples of local market risk is an investor of a large apartment complex located adjacent to a military base. The building was the most convenient location for military personnel to rent. This tenant base was ideal. They needed the rental, mostly paid rent on time, and respected others and the property. Unexpectedly, the military base closed. Because the property was centered on the military base, the cash cow apartment complex had problems with the next generation of tenants. The building went into bankruptcy a few times with a few different owners.

- Legislative risk. Not too long ago, federal and state laws allowed tenants to defer rents due to Covid. Some ways to qualify for deferral seemed random. Cities added their bent to these rules, getting high praise from local tenants. Meanwhile, the “greedy” landlords dealt with lenders, each tenant’s interpretation of these rules, etc. The process is not over, and many landlords will not be made whole. This risk was out of the owners’ control and caused some investor hardship and loss.

- Economic risk. I miss Circuit City! I imagine that their landlords miss them, too. The 59-year-old store declared bankruptcy in 2008, shuttering 567 stores with lease agreements. Some of those properties still aren’t fully utilized and have turned into seasonal Halloween, Christmas and costume shops. E-commerce has changed the landscape of retail investing. Warehouse investors love e-commerce. Fewer of our clients own these property types. But economic changes do impact other property types.

The list of real estate risks is longer. The point is that a client who has considerable equity in one of a few properties has more risk than someone who owns a basket of stocks. For example, when Circuit City closed, an investor with 50 stock positions, including Circuit City, might have permanently lost 2% of their investment. An investor who had Circuit City as a tenant lost considerable income and experienced negative cash flow. Since the value of a commercial real estate investment is based on its income, the investor also lost considerable market value.

The Big Question

I believe that the risk premium in real estate is high and is generally not a factor in determining the merits of an investment.

The question becomes, what is a good risk-adjusted rate of return for directly held real estate? The answer is, it depends.

When my wife and I were investing in real estate in the early 2000s, we were a part of an LLC made up of a small number of like-minded investors with similar investment criteria. The LLC was seeking an 8% internal rate of return, which included current income and market value growth. The managing member was experienced in skilled nursing facilities, so we looked at investing in them. Because these facilities reserved some beds for Medicare and Medicaid patients, the operator depended on reimbursement rules. This made legislative risk a factor.

Considering the various risks, we targeted a risk-adjusted internal rate of return at 12%. This means the investment had to perform higher than the base 8% return or we would not consider it. It would have been great to get this cash flow. But everyone understood that the risk of our holding was higher, and our analysis showed the investment would not achieve a 12% internal rate of return.

The point is that an investor needs to consider risk, as well as many other factors, in setting an appropriate return for each property. When a client asks whether a 4.5% risk-adjusted return a “good idea” for a real estate investment, your answer should be, “It depends.”

Some Perspective

Another frequently asked question is “What is a good annual yield for real estate?” Here is some perspective on what others are getting:

- According to the JP Morgan Guide to the Markets 2022, the average return for publicly traded real estate investment trusts (REITs) over the past 20 years is 11%. This strong return is not a good comparison to directly held real estate and annual yield. REITs trade daily and returns include fund income and growth. They may be more appropriate for someone who wants to diversify their equity holdings and is not focused on buying directly held properties.

- Income from institutional-quality real estate (which offer millions in equity for each building) can range from 4% to 6%. These properties are subject to many of the same risks you read about in real-estate fund prospectuses. So, these are not risk-free investments. Some syndicators and funds promote income higher than 6%. Some will deliver this without too much drama. Many will take on a much higher risk profile than investors would expect. In real estate, a small increase in yield can mean a significant jump in risk. Unlike a basket of stocks, this risk is usually not offset with investments in other properties.

- In our work, we have used client data and tax returns to create over 1,000 cash-flow analyses. Most of these are smaller properties have less than $3 million in market value. The yield range for most of these properties is 1.0% to 3.5% before personal income taxes (and tax-shelter benefits).

Final Thoughts

Advisors should consider a few more points:

- The definition of performance for directly held real-estate investments is subjective, even though you can quantify that performance.

- If you choose to help a client improve their current situation and achieve their goals, seek to understand their priorities and preferences first. While doing so, suspend what you know and believe.

- Advisors can help real estate-heavy investors and still operate a profitable business. This help can significantly improve a client’s long-term financial condition.

- When an advisor takes a client through a quality real estate conversation, the advisor creates deeper trust. You can affirm and reframe their interest to help them learn and grow, as well as make better financial decisions.

Rich Arzaga, CFP®, CCIM, helps financial advisors in areas they prefer to delegate; insurance reviews and directly-held real estate investing. He is also a long-time, honored instructor in the UC Berkeley Personal Financial Planning program. Rich teaches insurance and real estate CFP CE courses, Real Estate Investments for Financial Planners (15 hours of CFP CE), and Insurance for Financial Planners. Rich is the founder of the fiduciary-center insurance advisory firm The Insurance Whisperer and the founder of real estate planning firm The Real Estate Whisperer. For questions or suggestions on future articles, you may contact Rich at richarzaga@berkeley.edu.