Financial advisors intent on managing a slice of the tens of trillions of dollars in wealth leaving the accounts of high-net-worth individuals over the next few decades need an innovative planning strategy for their older, wealthy clients.

While $3 trillion of wealth is already in motion on an annual basis, analysts at Cerulli Associates expect $124 million to eventually makes its way to younger generations or philanthropy over the next 25 years. More than 80% of this wealth is coming from baby boomers and older generations. About $18 trillion will go to philanthropy, while $105 trillion will head to younger generations, with 80% of that amount landing in Generation X and Millennial households. Yet more than $50 trillion will first be passed laterally to surviving spouses, a large majority of whom will be women, before being passed to children.

“When we talk to advisors about wealth transfer, this idea of utilizing a more advanced planning strategy is really step one,” said Chayce Horton, senior analyst, high-net-worth wealth management, at Cerulli Associates. “It’s like putting on your oxygen mask first before helping others. Before you prospect your client’s family or anybody else that may have a stake in their estate, you first really need to make sure that the primary client has all of their potential needs fulfilled.”

“When we talk to advisors about wealth transfer, this idea of utilizing a more advanced planning strategy is really step one,” said Chayce Horton, senior analyst, high-net-worth wealth management, at Cerulli Associates. “It’s like putting on your oxygen mask first before helping others. Before you prospect your client’s family or anybody else that may have a stake in their estate, you first really need to make sure that the primary client has all of their potential needs fulfilled.”

And these needs are becoming increasingly complex, expanding beyond investment management to envelope financial planning, tax planning, trust services, philanthropic planning and even family counselling. Horton spoke at the research and analytic firm’s January 29 webinar “Preparing for the Great Wealth Transfer.”

Factors Behind the Surge in Wealth

This so-called great wealth transfer — which is reshaping the wealth management industry — has been created by three primary factors: the concentration of wealth; wealth increasingly being held by older households; and a doubling of wealth over the last dozen years.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, households classified as high-net-worth ($5 million or more in investable assets) have increased their share of wealth in the U.S. from less than one-third, to about half of all wealth, said Horton. “We’ve seen this have a huge impact, broadly from a social perspective, but also in the context of wealth management firms and advisors.” Those firms that tailored their team structures and service strategies around a more affluent client base have achieved “levels of growth that are multiple percentage points higher than those who haven’t been able to do that actively,” he added.

Householders older than 60 now control two-thirds of the wealth in the U.S, up from about half during the 2008 financial crisis. And the surging capital markets, even on an inflation-adjusted basis, has led to a doubling of wealth in the last dozen years, without accounting for market performance in 2024.

After spouses, financial advisors typically have the greatest influence — even more so than lawyers, accountants or business associates — on how affluent individuals choose to organize their estates. “So, the industry has a major role to play in the ongoing wealth transfer,” Horton added.

In response to a question by Bing Waldert, Cerulli’s managing director of U.S. research, Horton said family offices are now moving the fastest to acquire market share with high-net-worth and ultra-high net-worth investors. The higher end private banks and wirehouses are also expanding centralized services for multiple generations of a family while broker-dealers expand these resources for their advisors. “And a part of going after high-net-worth clients is being able to serve them on an intergenerational basis,” Horton said.

Expanding the Relationship with the Family

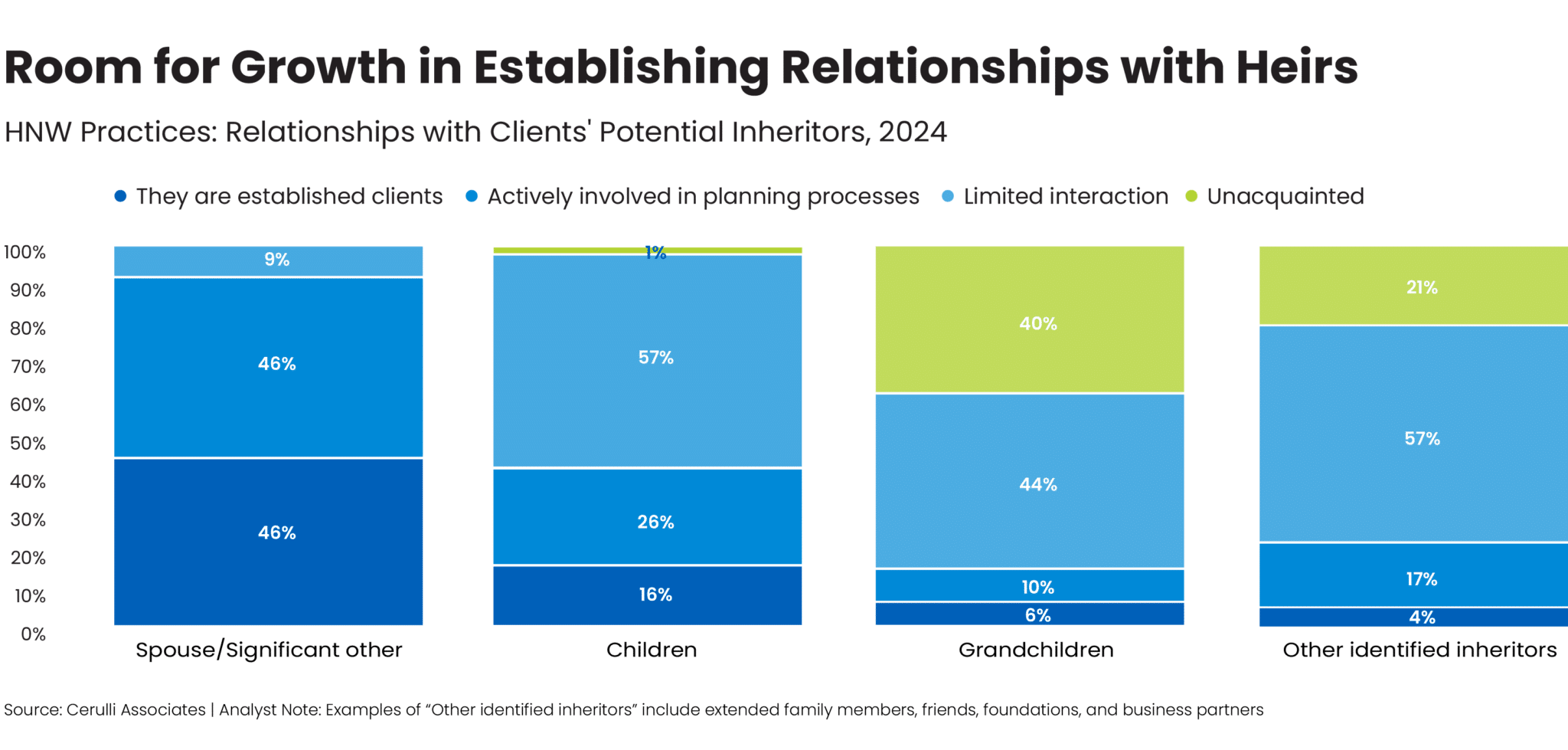

After satisfying the needs of the primary client, financial advisors must expand that relationship to envelop the entire family. “We see over $1 trillion going to surviving spouses already on an annual basis,” said Horton. More than 90% of the practices focused on high-net-worth individuals report they are actively involving the client’s spouse or significant other in the financial planning process, he added.

Yet there is a deficit on interactions with the client’s children. “And we think this is a huge opportunity … considering nearly $2.5 trillion in wealth is moving on an annual basis to these stakeholders already,” he said, adding that having the client initiate contact with other family members is most effective. Maintaining regular meetings and communications with, and amongst, family members is important. This can help with succession planning, whether in a family business or within the family itself.

“That can also be really imperative in maintaining continuity across generations,” said Horton. “And I really don’t think that’s something that can be done early enough.”

Client education is a good second step during the early stages of building relationships with spouses and children as these stakeholders will have different views on wealth than the primary clients. For example, including charitable or philanthropic advisory can be a good step, to find a point of interest for people less interested in the allocation of the portfolio, or nuances of the estate plan.

Meeting the Needs of Women and Younger Generations

In addition, wealth management firms need to change their traditional methods of doing business to meet the needs of women, who, as surviving spouses, will be the initial inheritors of about $50 trillion over the next two decades. Already, $1 trillion is moving annually to widowed spouses.

Eventually, as the wealth transfer lands in Generation Z households, women will reconsider who manages that money and with whom they want to work. Data shows that women care much less about investment performance or fees, and slightly less about staff, reputation or products and services, than men. “Most of the time they choose to work with an advisor whom they already know, already trust and already have a relationship with,” Horton said. “Financial advisory firms need to bring on more women advisors,” as the data shows five out of every six advisors are men.

Cerulli recommends that advisors broadly consider a more diverse set of needs when working with the next generation, as well as women. There is no one demographic characteristic of an inheritor, added Horton. “Inheritors can be as old as 60 or 65, or as young as 18 or even younger,” he said. “It’s important to be able to have a wide set of products that you can tailor, and a wide set of services and experiences that you could tailor to the individual client.”

For example, while older clients will be interested in traditional face-to-face meetings and an all-in-one service model, younger investors are more digitally native with experience in self-service models, and may work with an advisor for only certain tasks.

The overall convergence is a good sign for the industry as more advisors will have access to the resources needed to provide clients with the services they are increasingly demanding as part of the wealth transfer. “And better entrepreneurialism and better economics of being an advisor will help attract more talent to the industry,” said Horton.