Although more than half of Americans who turn 65 will need long-term care before they die, many are unprepared for these costs that may accompany aging. They’re also anxious about their ability to afford this essential care and confused about the insurance market that provides coverage. At a recent webinar sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, three speakers laid out Americans’ common fears, current market conditions and how public policy might help people best handle this risk.

“There is a lot of anxiety and confusion,” said Liz Hamel, director of public opinion and survey research at KFF, a health policy organization based in San Francisco. “And the lack of preparation may be contributing to this anxiety.”

Pointing to the results of the KFF Survey on Long-Term Care and Support Services, she said 66% of Americans are anxious about being able to afford the cost of a nursing home or assisted living facility. And fewer than half of adults age 65 or older say they have taken steps to plan for any care needs that emerge as they age.

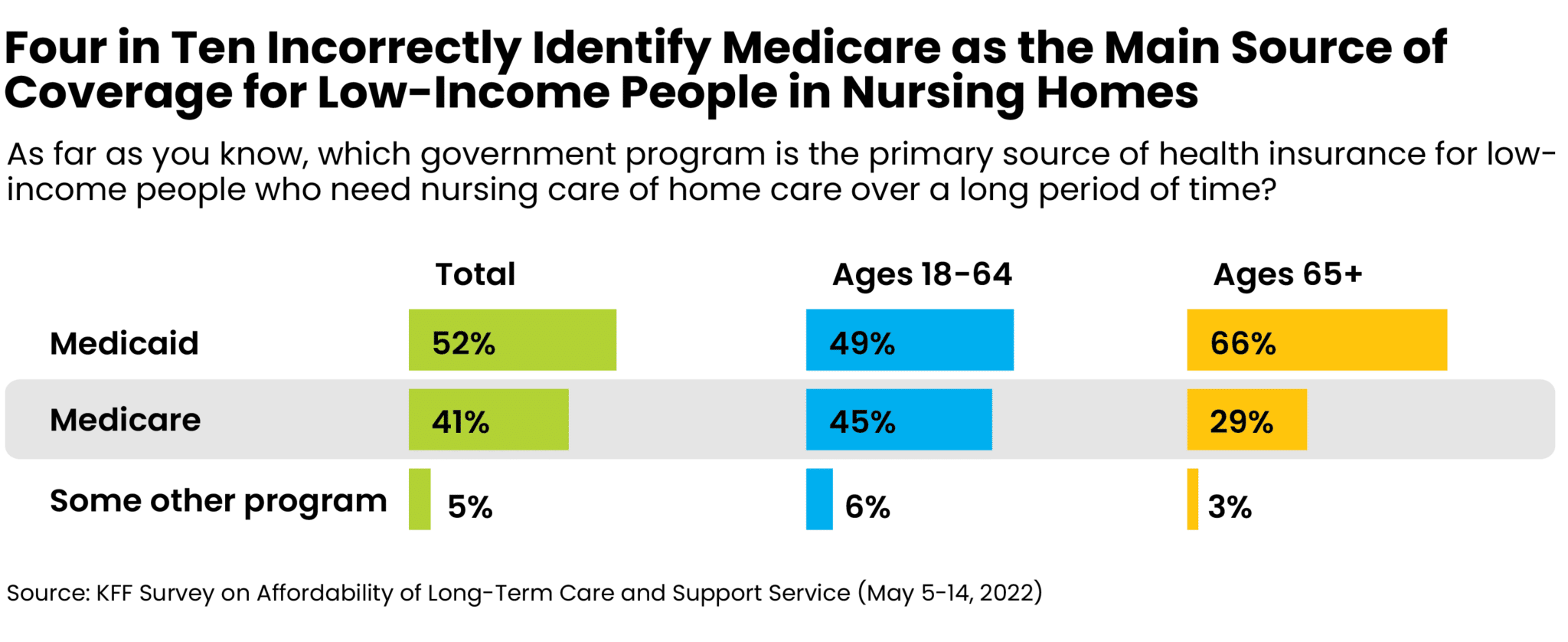

At the same time, Americans are confused about current market conditions, with four in 10 incorrectly identifying Medicare as the main source of coverage for low-income people needing nursing or home care over a long stretch of time. “There is a lack of understanding on how long-term care is financed in the U.S.,” added Hamel.

The KFF survey included 1,573 interviews carried out online and by phone in English and Spanish in 2022. KFF, formerly known as the Kaiser Family Foundation, is an independent source for health policy research, polling and news.

‘Men Die and Women Fade Away’

Karen Kopecky, economic and policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, opened the webinar, “The Cost of Longevity: Long-term Care Insurance in the U.S.,” by laying out current conditions in long-term care, which is chiefly nursing care to help a person with everyday activities, such as bathing and eating.

While overall 53% of Americans at age 65 will need long-term care before they die, women are more likely to require care than men. Fewer men (47%) than women (58%) meet the definition of need outlined by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPCC).

“I like to say that men die and women fade away,” said Kopecky. The average years of care needed for men are 3.2 while women need 4.4 years.

While informal care by relatives is common, the risk of needing expensive formal care is significant, with 45% of 65-year-olds needing formal long-term care before they die, Kopecky also noted.

Coverage Costs are Significant and Risky.

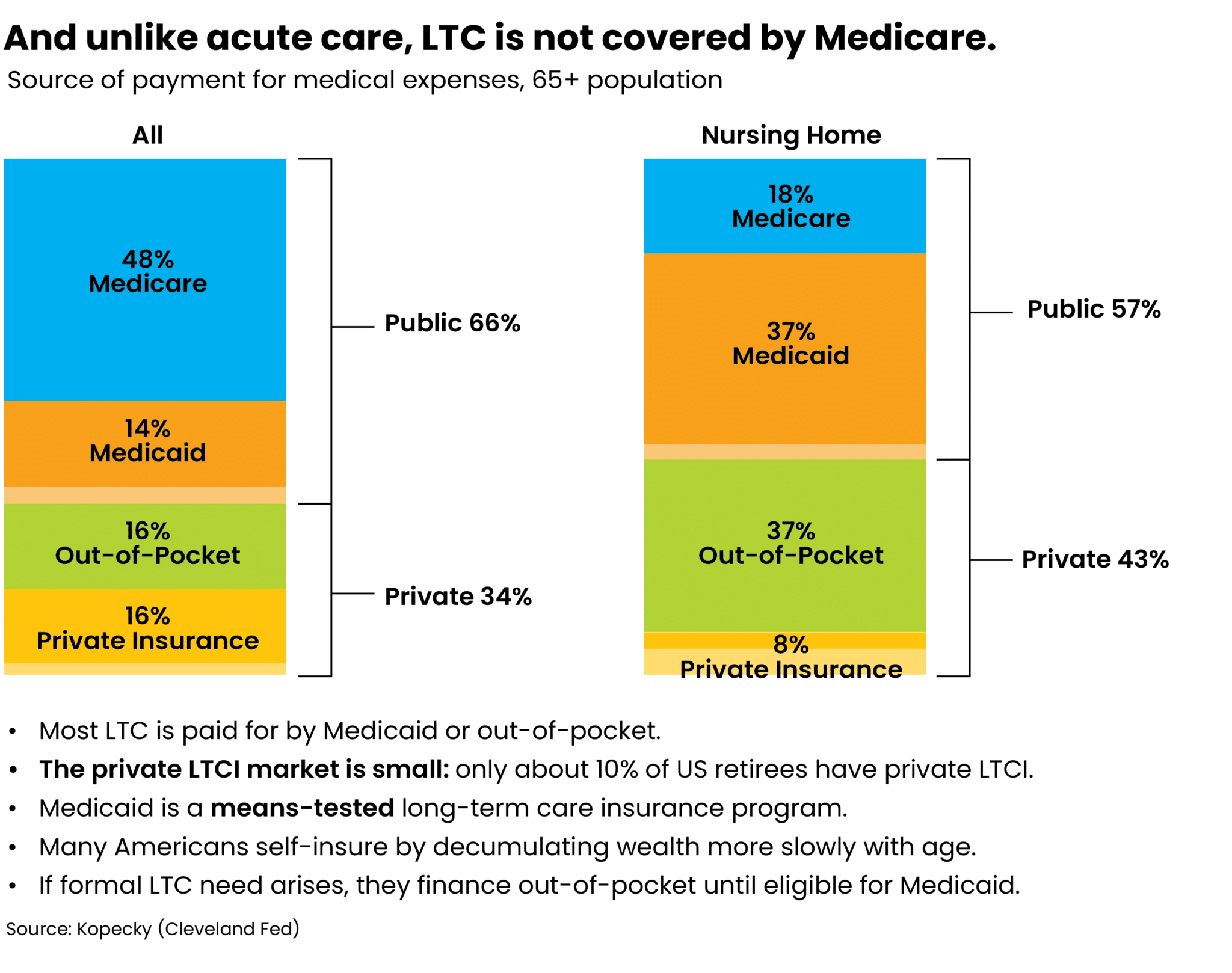

According to a 2024 Genworth Cost of Care Survey, the average annual median cost per person for assisted living is $54,000; in-home health care is $61,776; and a private room in a nursing home tallies $108, 405. Most long-term care is paid for by Medicaid or out-of-pocket and only about 10% of U.S. retirees have private long-term care insurance, Kopecky said .

“The private long-term-care insurance market is small,” said Kopecky. One reason is Medicaid, a means-tested long-term-care insurance program, crowds out demand for private insurers. For some people, private coverage is either too expensive or too risky to purchase. Average premiums are large with incomplete coverage and the average duration from purchase to initial claim is more than 20 years. “And if you never have a qualifying claim, you never collect benefits,” said Kopecky.

In addition, policyholders usually experience two or more rate hikes over the life of their policy. In 2019 Genworth Financial, for example, received 120 approvals by state regulators to raise premiums, and the weighted average rate increase was 45%, Kopecky noted.

Can Public Policy Help?

Anton Braun, a senior professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, a research graduate school in Tokyo, discussed how public policy might influence the long-term-care insurance market and help people prepare — and cope with — the need for long-term care.

“Many people don’t want to think about long-term-care risk … let alone take actions,” said Braun. “Why? The insurance is expensive. Medicaid benefits are only available to the destitute. And it is difficult to ask family members to commit to helping out.”

“Yet public reforms are going to be challenging because there is lot of disagreement among different groups in American society on what good policies are,” said Braun, who is also a senior fellow at the Canon Institute for Global Studies, a think tank based in Tokyo.

Three Strategies

Based on models developed by Braun and Kopecky, Braun laid out three strategies for reforming the long-term-care insurance market. The first strategy centers on dramatically scaling back public insurance by reducing Medicaid long-term-care benefits. “Medicaid now crowds out private insurance and by scaling back Medicaid, this could help develop a large, healthy and profitable private insurance market,” he said.

A second strategy goes in the other direction by offering universal public long-term insurance, This coverage could be included, for example, in Medicare rather than Medicaid. This would kill off the private market while helping middle- and low-income households. “It is good for them as they are getting coverage,” Braun said. But he added that affluent households would be worse off as they face higher tax bills to finance the program.

A third strategy is to enhance incentives for households to purchase private long-term-care insurance by easing the asset qualification test for Medicaid. “This strikes a consensus and there is less disagreement among different income groups and exposure groups,” Braun said.

This third option helps create a vibrant private insurance market without impacting most low-income people. Middle- and high-income people are much better off and can purchase so-called skinny private long-term-care policies that can cover a long-term-care event.

New Options

Public policy can also be used to enable the development of new private insurance options, Braun explained. For example, policy reforms could bring employers into long-term care by exempting taxes on distributions from employee 401(k) plans that are used for long-term-care expenses.

Noting that the Finra Financial Literacy Quiz and many studies show half of American don’t have the financial literacy skills for retirement planning, Braun supports efforts to have high schools and colleges become more involved in teaching financial planning as a life skill.

“Half of the American don’t have the financial literacy skills needed for retirement planning,” he said. “They aren’t even talking about saving for a long-term-care event.”