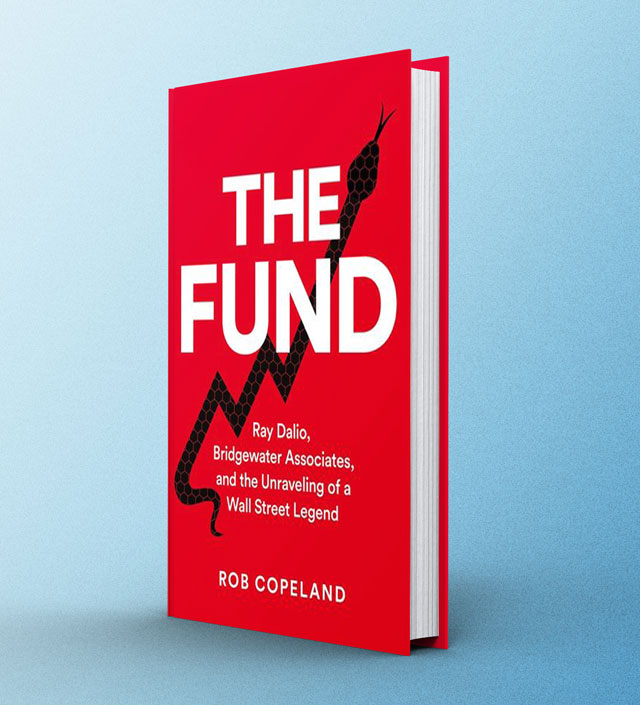

You might need to fling open a window for fresh air after reading “The Fund,’’ Rob Copeland’s smack-down of Ray Dalio, retired founder of the largest hedge fund in the world, Bridgewater Associates.

Copeland, former Wall Street Journal hedge fund beat reporter, chronicles the cult, or culture as Dalio called it, of Bridgewater, which featured Dalio humiliating and debasing employees, as he said, for their own good.

“Pain + Reflection = Progress,’’ Dalio explained in his collection of 400-plus Principles, mandated reading for all employees and later, the basis of a best-selling book.

A little pain and reflection among Bridgewater employees, Dalio maintained, was also good for investors.

“Dalio’s triumph was neatly exemplified at year end-2020, when researcher LCH Investments ran the numbers and determined the firm had made more money for investors, since its inception, than any other fund, a staggering $46.5 billion. Business Insider took the opportunity to call Bridgewater ‘the best performing hedge fund manager of all time,’” says Copeland.

“Though Bridgewater’s assets under management slowly contracted, from a peak of around $160 billion to $130 billion in the post-pandemic period, Bridgewater was so impressively larger than any other rival — and so willing to collect money from virtually any corner of the earth — that it could shrink and still credibly be described as the globe’s largest hedge fund,’’ writes Copeland.

This was certainly good for Dalio, 74, whose personal wealth is estimated at $20 billion by Forbes and $15.7 billion by Bloomberg News. Dalio founded the firm in 1975, operating out of his New York apartment, and retired in 2022. He maintains a position on the board of the company, located in Westport, Conn.

Why Did They Stay?

But with all the giddy numbers and stratospheric success, it’s likely that even readers willing to give Dalio some slack will have to fight back revulsion starting at about the one-third mark of the book. From that point on, depending on one’s tolerance for tales of bullying and sadism, “The Fund’’ will either make for juicy reading or wear one down.

On page 86, Copeland recounts Dalio’s warbling of a favorite sailors’ ditty, with verboten four-letter words included, about a prostitute with a vagina needing help from a mechanical device. The results are disastrous, leaving the sliced prostitute covered in her excrement. Dalio sang it from memory, to employees at a company gathering. While he sang, his top two women executives recoiled, one hiding in a bathroom.

Why, one wonders, did Dalio do this to employees he insisted he valued?

And why did employees stay at Bridgewater, after having endured a variety of humiliations, including “trials’’ where Dalio detailed an employee’s alleged faults, based on a ratings system said to apply to all, in front of hundreds of other employees. Some were fired on the spot, and the public drubbings were recorded, available for viewing on the firm’s Transparency Files. Dalio had a tech staffer rig the company’s computerized rating system so only he was excluded from being rated, Copeland writes.

If the assembled employees thought they might compare notes about the drubbing later, best they be careful: Cameras were everywhere, as were “whistle blowers’’ ready to report malcontents to gain a closer perch to Dalio.

A Climate of Fear

Copeland says the turnover was constant and sizeable, but there was always a crop of new college graduates, preferably from Princeton, Harvard, Dartmouth and Yale, new to the working world and intent on becoming rich at the world’s biggest hedge fund.

Older, wiser and even famous new hires gave Bridgewater a shot; the money was so good. But not good enough.

Technology executive Jon Rubinstein, who helped Steve Jobs create the first iPod at Apple, was hired by Dalio to transform his Principles into software and to be in charge of the iPad ratings system. Several months into his tenure, Rubinstein was “tried.’’ At a work party for his 60th birthday, he was eviscerated by senior management, but balked, and told the assemblage that Bridgewater’s biggest problem was The Principles, Dalio’s rule book.

As Copeland relays it, Rubinstein “called it a barely veiled weapon for abuse that created a climate of fear.”

After a few more months, Rubinstein left without fanfare, but with the remainder of his two-year compensation — about $50 million. He told friends that Bridgewater’s culture of radical transparency was “a fraud.’’

Dalio’s project to convert his Principles into software was wasted money, Copeland says.

“In late 2021, a move not publicly disclosed, Bridgewater laid off most of the remaining staff dedicated to building the Principles software. It was $100 million, at least, down the drain.’’

‘The Trial’ and Other Pastimes

Other hires carried out Dalio’s delegation of sadistic tasks with enthusiasm. In 2010, Bridgewater Associates hired James Comey as general counsel and head of security for $7 million a year. As a former U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, Comey prosecuted Martha Stewart for insider trading. Later, as director of the FBI, (before being fired by then-President Trump), he investigated presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s email account. At Bridgewater, Comey initiated an investigation into co-CEO Eileen Murray, whom he accused of lying about an email that defended a new hire, an old colleague of hers from Morgan Stanley.

“It wasn’t just a trial, it was the trial. The investigation of Murray went on for nine months,’’ Copeland writes, adding that Comey’s office walls were covered with newspaper clippings and sticky notes about Murray. The investigation was called “Eileen Lies’’ and was recorded for all to watch. Dalio invited his alma mater, Harvard Business School, to document the “trial’’ for an HBS course. He spent hours on the phone with an HBS professor editing the text.

“‘Doesn’t this guy have anything else to do?’ the professor wondered,’’ Copeland writes.

Good question. Copeland reports that Dalio spent much of his time when in Westport indoctrinating and controlling employees via his Principles, the company ratings system, the “trials,’’ and company gatherings fueled by alcohol and a zest for being part of the biggest hedge fund in the world.

He also spent big chunks of time traveling the world to woo clients, and succeeded in unlikely places like China and Kazakhstan. He gave TED talks, promoted his books, did interviews, played host at seminars and later, at webinars. His co-chief investment executives ran the investment side of things on a daily basis, under Dalio’s control.

Unanswered Questions

The professional Dalio jumps off the page, a villain of epic proportions but murky motives, unless one just concludes he’s a pathological bully. In this book, the personal Dalio is a cypher: We learn nothing about his marriage, although he has been married to Barbara Gabaldoni, a scion of the Vanderbilt-Whitney families, for 46 years. There’s nothing in his biography as presented here to indicate why he became so manipulative; an only child, he grew up in Manhasset on Long Island, went to C.W. Post College, and got his entrée into the world of finance by caddying for rich men who gave him stock tips on the golf course.

There are no quotes or anecdotes from or about his friends or about his family. His oldest son, Devon, died in an automobile accident in December 2020. That’s it for personal detail.

Copeland, now a finance reporter for The New York Times, tells us that in a CNBC interview, Dalio talked about his three favorite books, but Copeland doesn’t tell us what the books are; that would have been something to chew on.

It also would have been helpful if “The Fund’’ told us what it’s like at other highly successful hedge funds and financial firms: Is the Bridgewater culture unique, or is it typical of these intensely competitive companies with their ambitious masters of the universe?

There is this nugget, from Barclay Leib, the grandson of blue bloods George and Isabel Leib, who mentored the young Dalio and had him for Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners for many years at their Park Avenue co-op.

Years later, Dalio responded thusly to an email the Leib’s grandson sent, asking for Dalio’s good word at an upcoming Bridgewater interview:

If you are qualified for the job, then your resume should stand on its own. I would not undermine the process of my HR department for anyone.

I would not even offer such favoritism to my own dog if my dog were applying.

Ray.

The Fund. Ray Dalio, Bridgewater Associates, and the Unraveling of a Wall Street Legend, by Rob Copeland. St. Martin’s Press, 329 pages. $32.