Tumultuous markets, extreme volatility and portfolio losses cause anguish for investors. Last year’s historic rebound from the pandemic-related sell-off that began in March 2020 made investors complacent as markets posted new highs. And with 70 records set in 2021 for the S&P 500 Index, and the total comprising 63% of positive market closes, according to an article in Bloomberg, their complacency appeared to be justified.

Then this year, investors watched their previous three years’ gains melt away, as stock indices entered bear-market territory. Panic ensued, with many seeking the safety of cash. After all, isn’t cash king, especially when markets are plummeting?

Probably not, according to investment sage Warren Buffet.

“The one thing I will tell you is the worst investment you can have is cash. Everybody is talking about cash being king and all that sort of thing. Cash is going to become worth less over time … Cash is a bad investment over time,”the Oracle of Omaha said in 2014. Emphasis is on “less,” as 8.6% inflation eats away at cash’s current meager returns. If Buffet’s counsel was wise then, when inflation was a mere 0.8%, it’s even more so now.

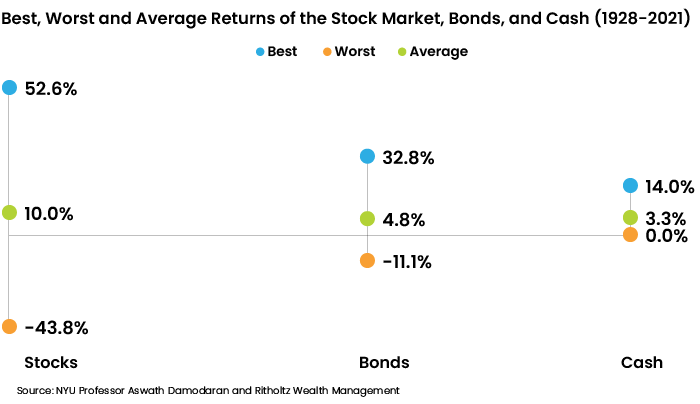

The chart below illustrates the outperformance of stocks over bonds for the past 93 years. The results have been impressive. Going back to 1928, when performance was first tracked, stocks have yielded an average of 10% annually. Over the period since then, investors have suffered sell-offs, but markets eventually recovered, although with a large variability of stock market returns compared to bonds and cash.

Stocks, as measured by the S&P 500, had their best year in 1954, returning 52.6% to investors, but also suffered their worst calendar year in 1931, down 43.84%. And bonds, a safe-haven asset class, had their best year in 1982, up 32.8%, and their worst year in 2009, down 11.1%.

Although the wider range of outcomes in stocks may seem intimidating, $100 invested in stocks back in 1928 would have grown to $761,710.83 by 2021, assuming dividends were invested. That same $100 invested in bonds would grow to only $8,526.85. There is a price to be paid for earning 5.2% more than bonds on an annual basis—that price is called volatility.

Savvy investors shy away from cash, even when markets are roiling. Warren Buffet bought stocks in 2014 when Russia invaded Crimea, and he continues to do so now, believing that crises put stocks “on sale.” Yet many investors in recent weeks have sold stocks. Why is that?

The key to investors’ behavior is behavioral finance

Part of the problem is negative news — of which a plethora exists. The daily drumbeat of spiraling inflation, the Fed’s admission that inflation is anything but “transitory,” coupled with its reluctance to hike rates earlier, and the seeming stalemate in Ukraine have frightened investors. Emotions are driving their decisions, causing extremes in their investing behavior.

Investors, like most other people, have a need for emotional control. Some are overconfident and overactive, trading excessively when they would be better off holding. Others may hoard cash, feeling more comfortable on the sidelines as they leave large portions of their portfolio uninvested.

But investors’ hesitancy to invest may affect long-term returns, because history demonstrates it is nearly impossible to time the market. A JP Morgan study showed that a $10,000 investment in the S&P 500 Index in 1999 would have grown to more than $29,000 by 2018. But having no money invested in the index during the best 10 market days during those 20-year period pared the results to $15,000. Over the long run, emotional decisions can be costly. The 2022 JP Morgan Retirement Guide notes that a $10,000 investment in the S&P 500 index on Jan.1, 2002 would have grown to $61,685 by Dec. 21, 2021, but missing the 10 best market days during those years would reduce the results to $28,260].

Part of the problem is that investors are fighting their own psychology. They’ve been conditioned to believe that if they try harder, they will get better results. Though often true in sports, it doesn’t hold true in the complex world of investments, where things beyond investors’ control, like monetary policy and geopolitics, can affect companies’ pricing power and earnings.

Advisors recognize that managing their clients’ emotions is as important as managing their portfolios.

As many practicing financial advisors will attest, investing is as much a game of managing portfolios as it is of managing emotions. This is where a behavioral finance advisor can be of tremendous benefit – because they recognize that in the real world, human decisions often are influenced by emotions, biases and cognitive errors.

Advisors must understand how their clients react to market events and how that influences their decision-making. They can begin by framing messages to avoid costly mistakes, such as explaining that long-term decisions may feel uncomfortable along the way. They also can reinforce how a long-term approach to staying invested has been successful, and why it will continue to succeed in the future.

Act in concert with risk tolerance

Rather than succumbing to fear, clients can be encouraged to act in concert with their risk tolerance—making the best decisions rather than the most comfortable ones. [ITAL: “best” and “comfortable”] Advisors must go beyond the usual assessment of long-term objectives and the combination of asset classes that will help achieve them for the level of risk they are willing to take.

Understanding clients’ risk tolerance means delving into their attitudes toward risk: composure (emotional engagement); anxiety; reluctance (the degree to which they are able and willing to enter the market at all); decision-making style; and assessing their own skill level (versus seeking an expert’s advice).

Next, advisors can use data to help their clients assess their five-to-seven-year outlook. Although this encompasses understanding the risks in their portfolio, clients may be surprised to learn that most successful investors don’t focus on their portfolio every day. Fidelity conducted an internal review of clients’ accounts, and discovered that their best investors were either dead or inactive.

”Dead” referred to people who were deceased, with assets frozen while the estate was handling them. ”Inactive” clients had established a retirement plan, switched jobs, forgotten about the account and left assets in place. In essence, the less touch, the more money. Sometimes the best decision may be to do nothing.

Hold sufficient cash to feel comfortable during a market correction

After assessing risk, advisors can help clients determine the appropriate cash level they should hold. Based upon an analysis of market returns, stocks outperformed Treasury Bills 77% of the time, over five-year periods, since 1928, and were positive 88% of that time period. Over 10 years, stocks outperformed Treasury bills 85% of the time, and were positive 94% of that time period.

Holding too much excess cash results not only in loss of capital but erodes purchasing power, especially in a hyper-inflationary environment. Investors who are comfortable making money only 85% of the time may need to hold cash to cover five years of living expenses, the recommended maximum. Others, believing they can make money 90% of the time, may be comfortable with cash equal to two years of living expenses. (Both amounts are in addition to a six-month emergency reserve.)

Consider alternatives as a substitute for low-return traditional assets

Stocks and bonds both have been pummeled by surging inflation and escalating interest rates. Bonds have fallen 20% on a year-to-date basis, and stocks have lost value because rising rates curtail future earnings. Alternative investments can offer different sources for returns for income-oriented investors. Some examples as of June 2022:

- Private debt funds, geared to middle-market businesses, are currently yielding around 7.5% net of fees. Diversifying among solid companies, with no late payments, and using floating rate financing, make these vehicles attractive. They do carry risk: In a recession, loans would be marked down. But compared with cash deteriorating at the current inflation rate, it would be analogous to a flesh wound versus internal organ damage.

- Short-term real estate lending to developers, builders, or resellers for whom permanent financing is not available is currently yielding in the range of 6% for non-leveraged loans (currently 9% for leveraged ones). These loans emphasize multifamily housing, as higher mortgage rates reduce demand for single family housing. Investors’ capital is returned once the borrower obtains a long-term loan or sells the property. Risks include a recession, making permanent financing difficult to find, or the real estate market suffering a downdraft. However, the lender jointly holding title mitigates risks, as the property can be sold to recoup losses.

- Physical real estate lending, in which 80% of loans are spread between industrial and multifamily housing, with 20% in offices or retail, is currently posting returns of around 4%. This can be an attractive option for investors who want exposure to real estate but who prefer not to purchase single family homes outright. These properties may include warehouses, factories, senior housing, or student housing, all of which generate rents, with inflation hedges built into them.

In times of turmoil, investors are naturally inclined to retreat to the “safety” of cash. But present inflationary conditions make cash an imprudent choice, and evidence shows that over time, stocks outperform cash by a substantial percentage.

Advisors can help educate their clients to take advantae of opportunities inherent in volatility. Warren Buffet has earned billions for himself and his investors by purchasing stocks “on sale.” Income-oriented investors can find attractive returns in alternatives, such as private debt funds, short-term lending to real estate developers and builders, and in physical real estate lending.

Brian Chang, CFA is a Southern California based senior wealth advisor for Kayne Anderson Rudnick, an investment and wealth advisory firm managing assets for corporations, endowments, foundations, public entities and high-net-worth individuals.