How do you want your social media pages, smartphone photos and computer files handled after you die? While property and money distribution are usually at the top of the estate-planning list, don’t forget to leave instructions regarding your digital accounts and assets — so your survivors are left with more than just random bits and pixels from your online presence.

Here’s a short guide to getting your digital material in order, as well as advice for dealing with the accounts of those who departed without leaving directions.

Create a Digital Directive

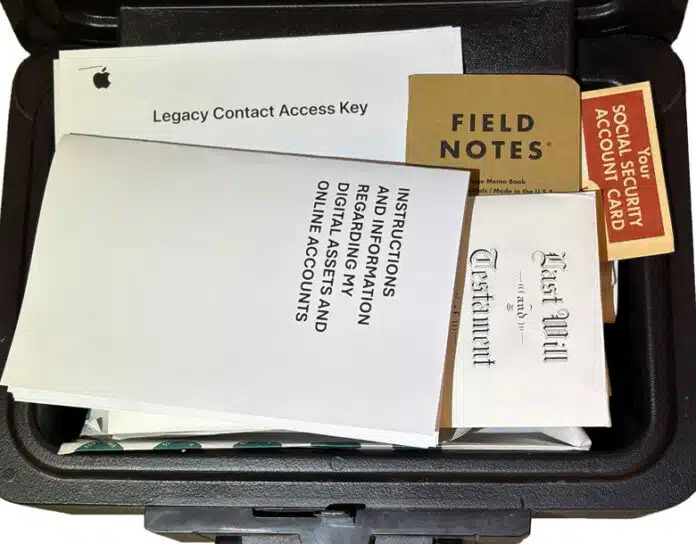

A law known as the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act, enacted by most states, gives a chosen representative (like your estate’s executor) the authority to manage your electronic affairs. For specific instructions, create a document stipulating how you want your online accounts and all digital content handled when you die or become incapacitated, and keep it with your other estate papers.

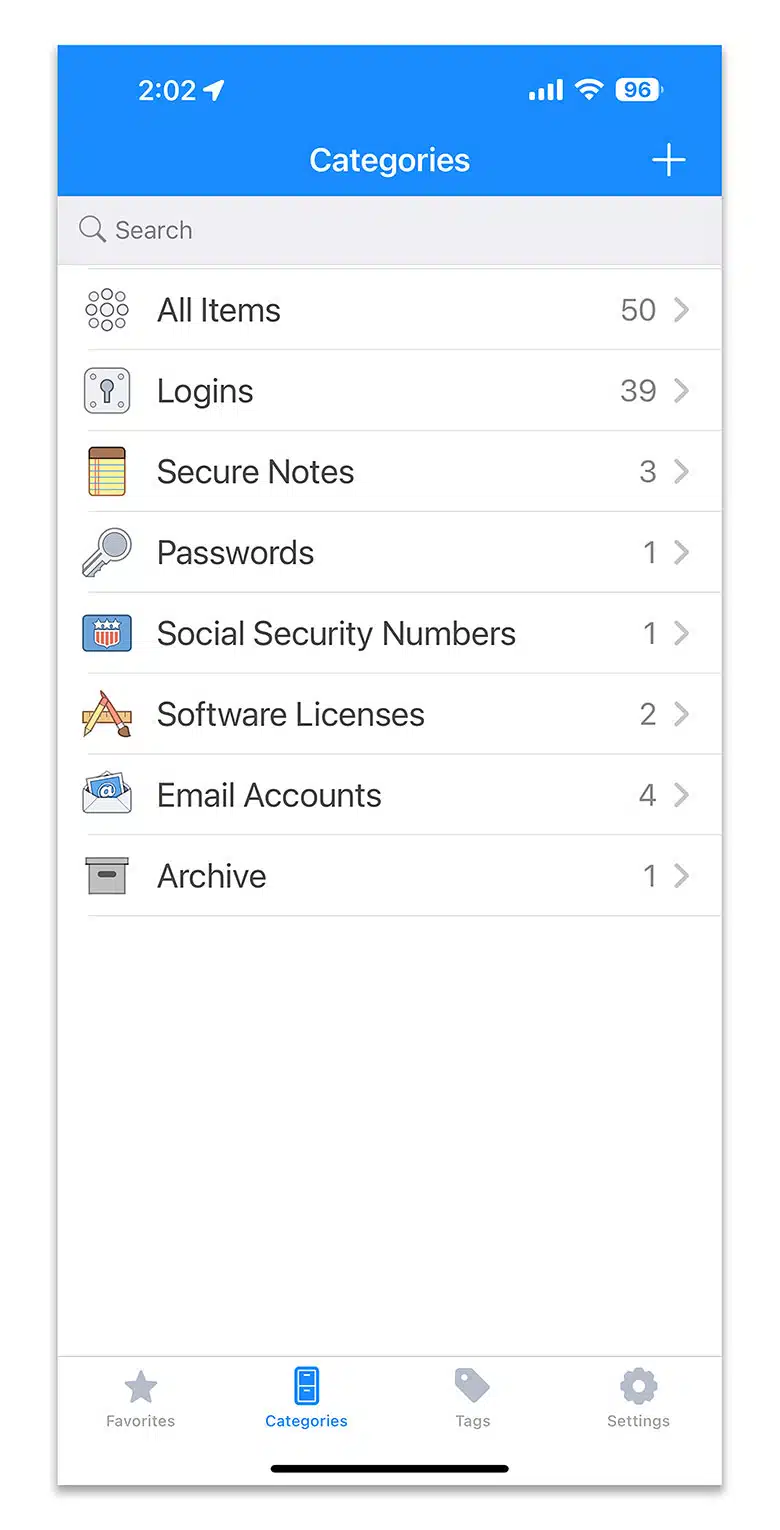

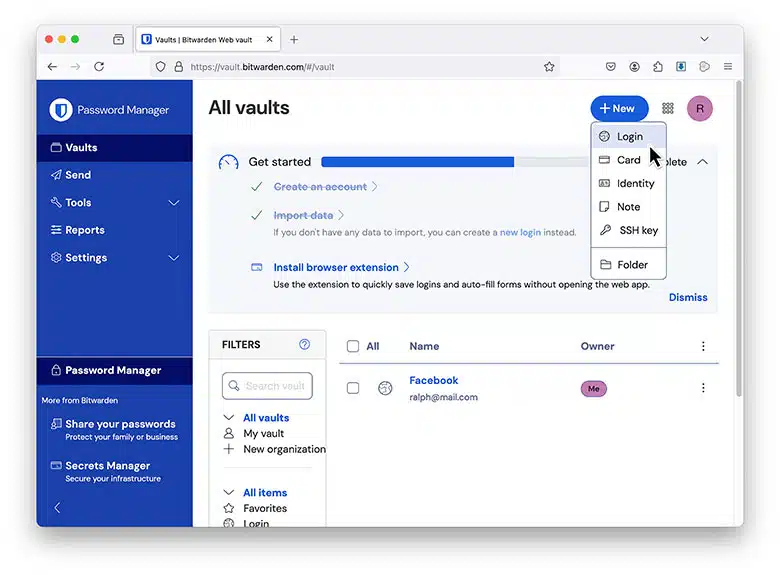

Giving access to your account usernames and passwords will greatly help your representative, but proceed carefully. You will need a safe place to list the credentials for all your financial institutions, as well as for any e-commerce stores, insurance policies, online storage, email, social media platforms, cable and wireless carriers, medical apps and media subscriptions.

One way to encrypt and store this sensitive information is to enter it all into a password-manager app. Wirecutter, the product review site owned by The New York Times, recommends 1Password ($3 a month for an individual plan, $5 a month for the shared family plan) or Bitwarden (free, with in-app upgrades). Apple and Google have their own free apps, which save and store passwords on devices running their software.

If you want an analog option, print out the list or write everything down in a notebook. Keep it updated, but make sure the list is locked in a home safe or another secured location, as it would be a gold mine for identity thieves.

Don’t forget to note the passwords and passcodes needed to get into your password manager app, phone, computer or tablet; most manufacturers can’t bypass a PIN code without erasing the device. Your survivors may need your contact list to tell people you’ve passed, and they may need to keep your phone accessible for any necessary two-factor authentication codes.

Designate a Legacy Contact

Along with compiling your digital directive and passwords, you should consider adding someone you trust as a “legacy contact” for your Apple, Google, Facebook and other accounts. A legacy contact is the person you choose to directly handle that account after you’re gone.

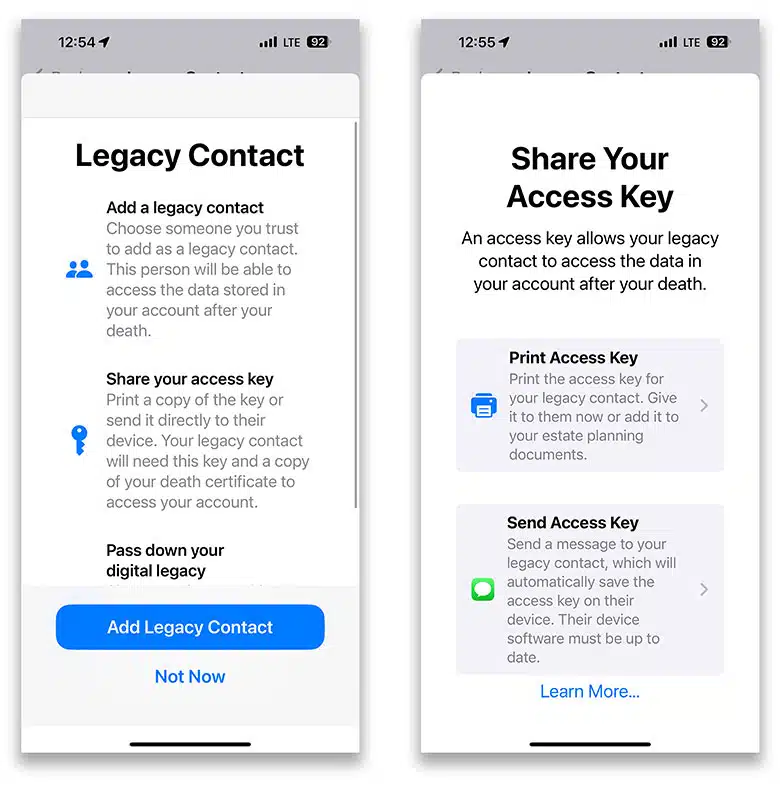

Apple added a legacy contact feature to its software in 2021 and lets you select a manager for your Apple account used with iPhones, iPads and Macs. To set it up, go into your system settings on the device or Mac, select your name and then Sign In & Security, and choose Legacy Contact.

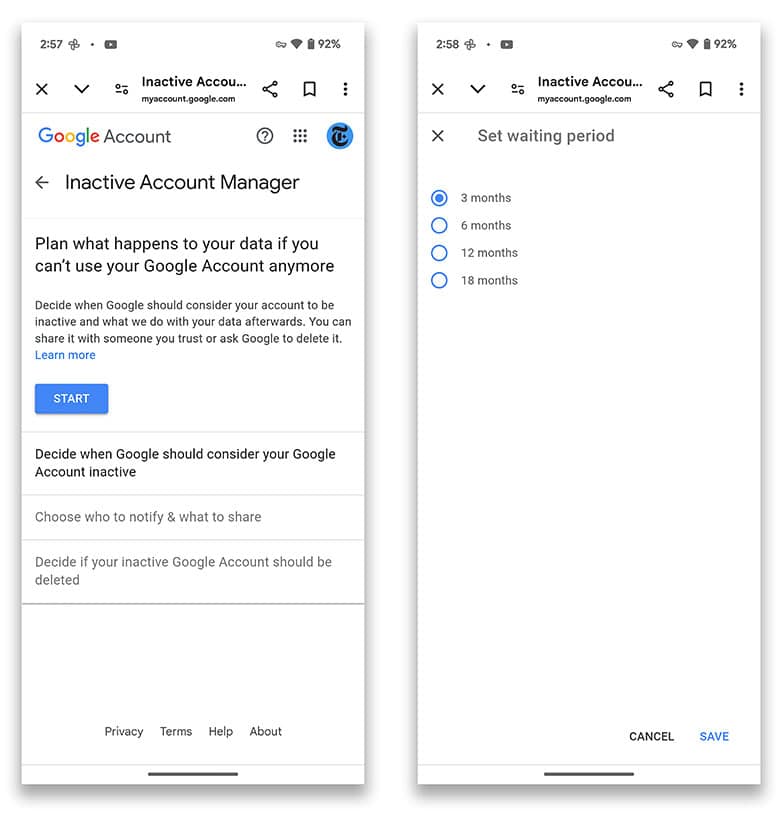

Google has an Inactive Account Manager tool for dealing with your Google Account if you are not able to use it. To set it up, visit the Data & Privacy settings of your Google Account.

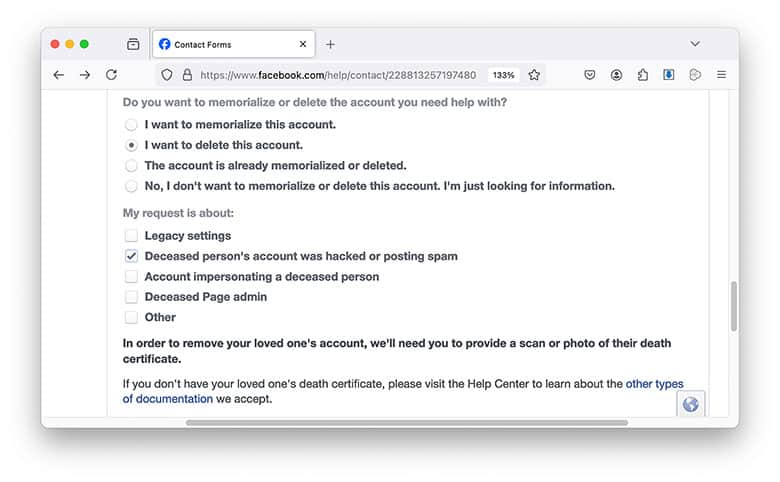

Facebook has a legacy contact setting for designating someone to manage your profile page, as well as a setting to delete your account when the company is notified of your death. For sites that don’t let you designate a person — and that you haven’t left instructions about — your executor typically must contact the company and request that the account be deleted or memorialized (converted to a static page).

Apple, Google and Microsoft are among those with account-deletion steps on their sites. Facebook, as well as other social sites, has a tool to download the photos and other content from an account before you delete it, as does Google with its Google Takeout feature.

Managing Without Instructions

On the other side of process, if you’re the person handling an estate for someone who didn’t plan for their digital legacy, your administration experience may take more time. But even if you did not receive instructions, you should try to shutter social-media profiles and other accounts to avoid misuse on the internet.

Just as you would inform financial and insurance firms of the person’s death, you should notify the social media and other companies and request that they close the deceased’s accounts. This typically requires providing a death certificate, an obituary, letters testamentary (court-issued documents given to an estate’s executor), your personal identification and other files. Digitized copies are often accepted.

The help sections of Instagram, LinkedIn, Microsoft, PayPal, X, Yahoo and other sites have instructions for account access and closures, as do those of Apple and Google. In many cases, you can request the account’s content like photos and posts, although this may require submitting even more legal documentation to the company.

Managing the digital assets of a deceased person without instructions can make a difficult time even harder — which is all the more reason to leave your loved ones everything they need.

c.2025 The New York Times Company. This article originally appeared in The New York Times.