The bulge on the side of Peggy Hudson’s belly was the size of a cantaloupe. And it was growing.

“I was afraid it would burst,” said Hudson, 74, a retired airport baggage screener in Ocala, Florida.

The painful protrusion was the result of a surgery gone wrong, according to medical records from two doctors she later saw. Using a four-armed robot, a surgeon in 2021 had tried to repair a small hole in the wall of her abdomen, known as a hernia. Rather than closing the hole, the procedure left Hudson with what is called a “Mickey Mouse hernia,” in which intestines spill out on both sides of the torso like the cartoon character’s ears.

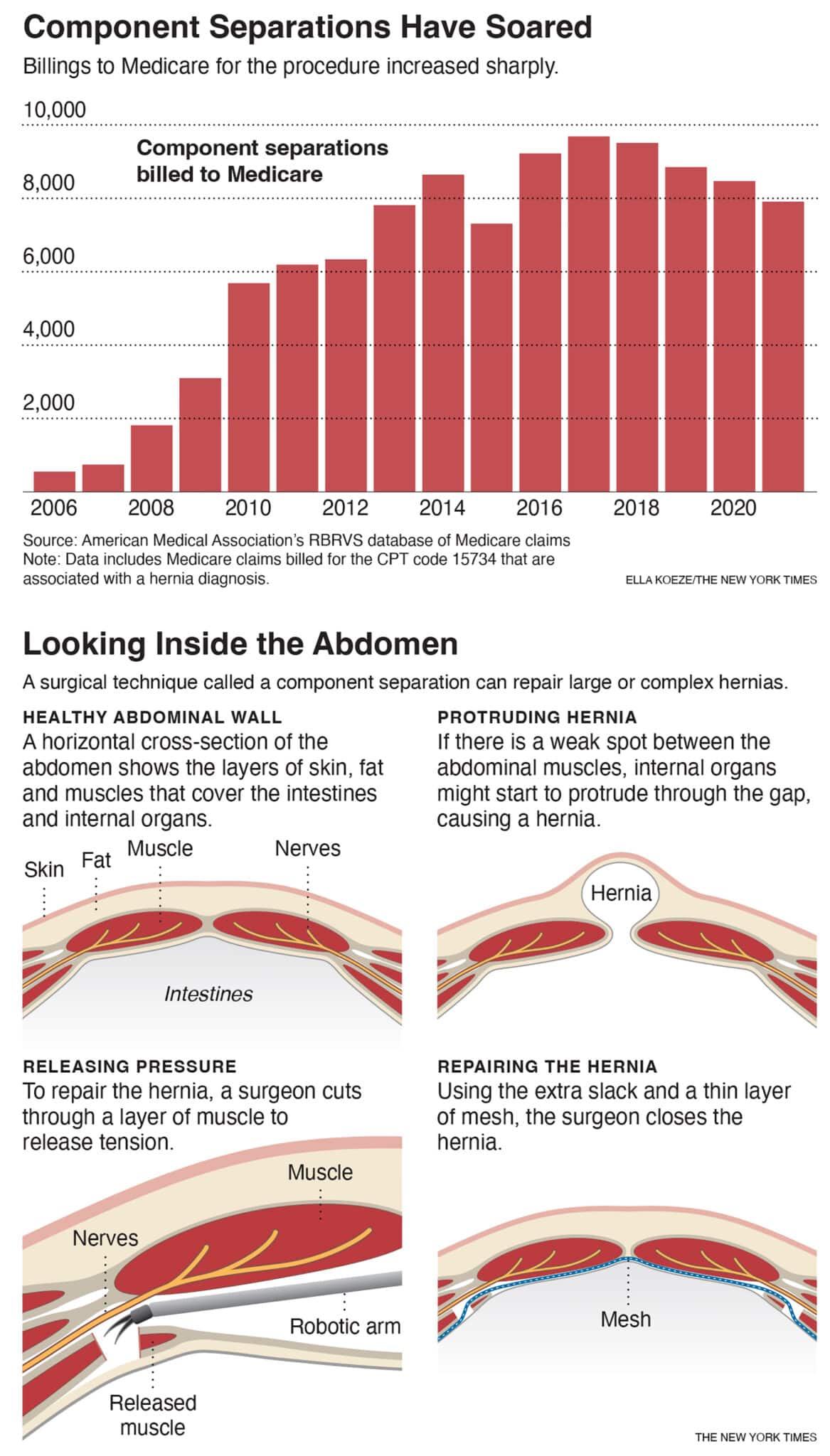

One of the doctors she saw later, a leading hernia expert at the Cleveland Clinic, doubted that Hudson had even needed the surgery. The operation, known as a component separation, is recommended only for large or complex hernias that are tough to close. Hudson’s original tear, which was about 2 inches, could have been patched with stitches and mesh, the surgeon believed.

Component separation is a technically difficult and risky procedure. Yet more and more surgeons have embraced it since 2006, when the approach — which had long been used in plastic surgery — was adapted for hernias. Over the next 15 years, the number of times that doctors billed Medicare for a hernia component separation increased more than tenfold, to around 8,000 per year. And that figure is a fraction of the actual number, researchers said, because most hernia patients are too young to be covered by Medicare.

In skilled hands, component separations can successfully close large hernias and alleviate pain. But many surgeons, including some who taught themselves the operation by watching videos on social media, are endangering patients by trying these operations when they aren’t warranted, a New York Times investigation found.

Dr. Michael Rosen, the Cleveland Clinic surgeon who later repaired Hudson’s hernias, helped develop and popularize the component separation technique, traveling the country to teach other doctors. He now counts that work among his biggest regrets because it encouraged surgeons to try the procedure when it wasn’t appropriate. Half of his operations these days, he said, are attempts to fix those doctors’ mistakes.

“It’s unbelievable,” Rosen said. “I’m watching reasonably healthy people with a routine problem get a complicated procedure that turns it into a devastating problem.”

Hudson’s original surgeon, Dr. Edwin Menor, said he learned to perform robotic component separation a few years ago. He said he initially found the procedure challenging and that some of his operations had been “not perfect.”

Menor said that he now performs component separations a few times a week and that, with additional experience, “you improve eventually.”

Component separation must be practiced dozens of times to master it, experts said. But 1 out of 4 surgeons said they taught themselves how to perform the operation by watching Facebook and YouTube videos, according to a recent survey.

Other hernia surgeons, including Menor, learned component separation at events sponsored by medical device companies. Intuitive, for example, makes a $1.4 million robot known as the da Vinci that is sometimes used for component separations. Intuitive has paid for hundreds of hernia surgeons to attend short courses to learn how to use the machine for the procedure.

Many surgeons — even some paid by device companies to teach the technique — haven’t learned how to properly carry out component separation with the da Vinci, the Times found. In fact, at times they are teaching one another the wrong techniques.

The robot comes with a built-in camera that makes it easy for doctors to record high-resolution videos of their surgeries. The videos are often shared online, including in a Facebook group of about 13,000 hernia surgeons. Some videos capture surgeons using shoddy practices and making appalling mistakes, surgeons said.

One instructional video, paid for by another major medical device company, showed a surgeon slicing through the wrong part of the muscle with the da Vinci.

Peper Long, a spokesperson for Intuitive, said the company hired “experienced surgeons” to lead its training courses. “The rise in robotic-assisted hernia procedures reflects the clinical benefits that the technology can offer,” she said.

In interviews with the Times, more than a dozen hernia surgeons pointed to another reason for the surging use of component separations: They earn doctors and hospitals more money. Medicare pays at least $2,450 for a component separation, compared with $345 for a simpler hernia repair. Private insurers, which cover a significant portion of hernia surgeries, typically pay two or three times what Medicare does.

As hernia surgeons were dabbling in component separation, a larger shift in surgery was underway: using robots to operate.

Intuitive debuted its da Vinci robot in 2000, with the idea that more precise surgery would shorten recovery times. Surgeons could remotely control the robot’s tiny clamps and scissors, allowing them to carry out complex operations with small incisions.

The company marketed the robot to a variety of specialties, including cardiology and urology.

Beyond traditional sales tactics, Intuitive also made inroads into the growing Facebook group, a lively forum where hernia surgeons discussed everything from troubleshooting tricky cases to complaining about their pay.

At first, the group’s members weren’t keen on the robot, questioning whether the flashy new tool was worth its steep price tag. “A lot of added expense with what perceived benefit to the patient?” one surgeon wrote on the Facebook group’s page in 2014.

Around that time, an Intuitive representative placed a phone call to Dr. Eugene Dickens, a general surgeon at a community hospital in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Dickens had grown up playing video games and was immediately comfortable at the da Vinci’s remote controls, which he used for dozens of gallbladder, appendix and simple hernia surgeries. Intuitive was paying him to be a consultant. (Since 2013 he has received about $1 million.)

Now the company wanted him to jump into the Facebook fray and win over the naysayers, he said.

He and other robot enthusiasts began to sing the da Vinci’s praises in the Facebook group, he said. (He said that Intuitive did not pay him for his Facebook posts.)

Over time, the group warmed to the robot, not just for simple hernia repairs but also for more complex operations like component separations. Surgeons began posting videos showing off the new procedure, drawing dozens of positive comments.

Surgeons used the da Vinci for more than 1.3 million hernia repairs between 2016 and 2022, Long said, or about 15% of the total procedures by the company’s robots. Only about 13,000 of those hernia repairs were component separations, she said.

Intrigued by the hype, Dickens taught himself component separation by watching online videos. His first operation went well, he recalled, but a later patient developed a serious complication, necessitating an additional surgery.

Then, at a dinner meeting in Houston, he presented a video of one of his own surgeries to a group of about 50 other doctors, Dickens recalled. A more experienced surgeon interrupted to say he was operating on the wrong part of the muscle. The rebuke felt like a “red flag,” he said, and he stopped doing the procedure, although he is still a proponent of the da Vinci for other operations.

In June 2021, W.L. Gore & Associates, a medical device company that makes surgical mesh used in hernia repairs, posted a video tutorial on its website. It promised to be a step-by-step guide to component separation surgery.

A surgeon narrated as he cut the patient’s abdominal muscles, releasing tissue so he could close a hernia. But he was operating in the wrong place and likely created a new hernia, according to four surgeons who reviewed the video.

“It absolutely trashed the abdominal wall,” said Jeffrey Blatnik, who directs the Washington University Hernia Center. “It was so offensive to the point that we reached out to the company and told them, ‘You guys need to take this down.’”

Jessica Moran, a spokesperson for W.L. Gore, said that after surgeons flagged the error, the company removed the video; it had been online for 10 months. “We have investigated what happened here to avoid this happening again in the future,” Moran said.

Dr. Rodolfo Oviedo performed the faulty surgery. Moran said the company had paid him $4,400 for it.

Oviedo acknowledged that he had made mistakes but said he had improved. “At some point I was doing it wrong, and nobody’s perfect,” he said in an interview in June, when he was the director of robotic education at Houston Methodist, a major hospital in Texas. He said it was only at some point after the surgery that he learned of his potentially serious errors.

Four months later, Oviedo offered a new explanation. He said that he had learned of his mistake in real time and had repaired the damage while the patient was still on the operating table. He said the patient, with whom he followed up for 18 months, had not experienced complications.

W.L. Gore’s video had plenty of company: A study of 50 highly viewed hernia repair videos on YouTube found that 84% did not follow all safety guidelines.

c.2023 The New York Times Company. This article originally appeared in The New York Times.