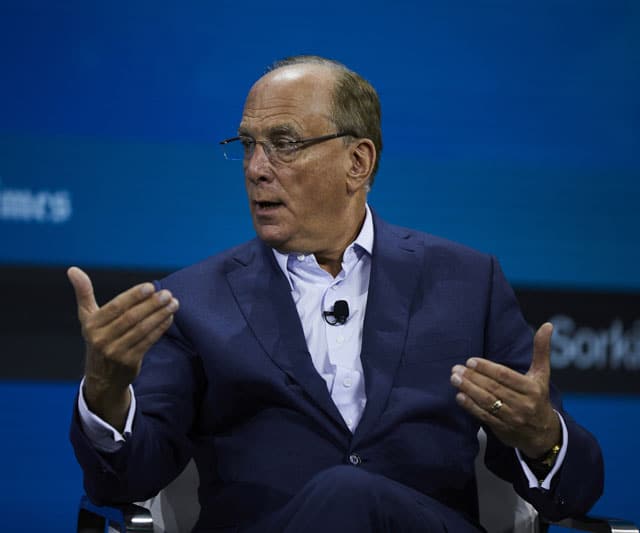

For years, Larry Fink, the chief executive of the giant asset manager BlackRock, has been broadcasting a message to corporate America: Environmental, social and governance goals should be core to how companies do business.

So when BlackRock announced in July that it would appoint Amin Nasser, the head of the world’s largest oil company, Aramco, to its board, investors and politicians immediately called out Fink on what they said was his hypocrisy.

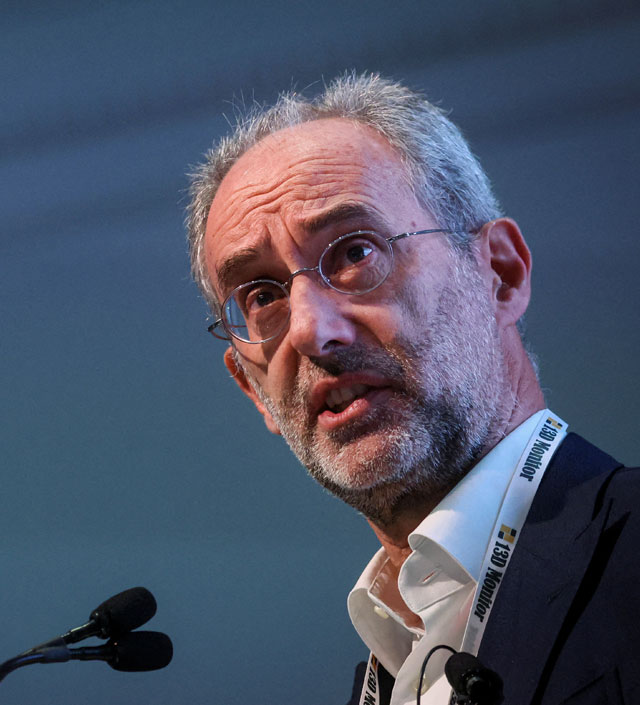

“This is out of line with everything BlackRock has been saying for the last five years about being a leader in the green economy,” said Giuseppe Bivona, the chief investment officer of Bluebell Capital, a hedge fund in London, which has been calling for Fink’s ouster over his handling of investments in fossil fuel companies.

It’s the latest example of the increasingly difficult situation Fink finds himself in: His championing of ESG has drawn accusations of “woke” capitalism from the right, while his embrace of energy companies has upset those on the left. The political blowback has made it more challenging for Fink to do his day job of finding new sources of money that BlackRock — which oversees $9 trillion in assets — needs to drive growth and keep shareholders happy.

“As one should expect, Larry follows the money,” said Terrence Keeley, BlackRock’s former head of the official institutions group, which oversaw sovereign wealth funds, pensions and central banks. “Soon Saudi Arabia will have the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world,” said Keeley, who runs 1PointSix, an advisory firm.

Courting oil money from the Middle East is not new for Fink, but Nasser’s appointment is the latest and potentially most important effort to deepen those ties, given the gusher of cash that Saudi Arabia is eager to spend, analysts said.

BlackRock has had board members from Middle Eastern countries since 2008. The state-backed investment funds of Saudi Arabia, Abu Dhabi, Kuwait and Qatar are flush with hundreds of billions of dollars earned from selling oil to the world, and they are active investors. Fink has pushed those sovereign wealth funds to become shareholders of BlackRock. It has also partnered with them to make private investments, which are usually more profitable than BlackRock’s traditional business of exchange-traded funds.

BlackRock declined to make Fink available for an interview. It said in a release that Nasser’s more than 40 years at Aramco “gives him a unique perspective on many of the key issues facing our firm and our clients.” Aramco declined to make Nasser available for an interview.

The decision to add Nasser riled Brad Lander, the New York City comptroller.

“At a time when financial institutions need to take a collective approach to addressing the financial risks from climate change, BlackRock shareholders expect climate-competent, not climate-conflicted, directors,” Lander said in a statement. New York City’s pension funds have roughly $250 billion under management.

Fink, who co-founded BlackRock in 1988, began talking about ESG some years ago. In his 2020 annual letter to chief executives, he wrote that BlackRock would be putting “sustainability at the center of our investment approach.” In bold font, he added: “Every government, company and shareholder must confront climate change.”

Lately, Fink has been forced to defend — and even de-emphasize — his stance on ESG. Many senior Republican leaders have criticized what they deem BlackRock’s activist investing. Last year, some state pensions pulled what amounted to several billion dollars in assets, although BlackRock said it added hundreds of billions in new U.S. pension assets.

The left has also pounced on Fink. Climate activists regularly protest in front of BlackRock’s New York headquarters, criticizing the firm for undermining its push to fight climate change.

Fink, 70, said at the Aspen Ideas Festival in June that he had stopped using the term ESG because it had been “weaponized” by politicians. BlackRock also spent much of 2022 reminding the world that its “clients are some of the largest investors in the energy industry.”

BlackRock, like its peers, built much of its business by offering low-cost index funds, which account for a majority of its business and continue to grow. But unlike Vanguard and Fidelity, Fink has pushed the asset manager to invest in more profitable areas like advisory work, risk management, infrastructure and alternative assets.

BlackRock’s strategy has rewarded investors over the long term. At the end of 2022, its stock was up 7,700% since its public offering in October 1999, compared to 365% for the S&P 500 stock index. Its market capitalization is nearly $110 billion.

For investors, a key value for the company is its ability to garner more assets and increase revenue — something that becomes more and more challenging given BlackRock’s size. Compared with BlackRock’s $9 trillion, two of its two closest rivals, Vanguard and Fidelity, manage roughly $7 trillion and $4 trillion in assets.

Michael Brown, an analyst at KBW, an investment banking firm, wrote in a recent research note that BlackRock warranted a valuation above its peers because it had more opportunities for growth.

Fink has told BlackRock employees and others that the Middle East — and Saudi Arabia in particular — is important to the future of the firm.

Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund is one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world, with an estimated $777 billion, mostly from its holding of Aramco stock, according to the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute. Having started investing outside of Saudi Arabia only recently, it’s one of the most untapped funds in the world.

Additionally, the kingdom is making giant investments in infrastructure within its borders, even building a new city from the ground up. BlackRock has both invested in and advised on some of these projects.

When BlackRock announced Nasser’s appointment, the firm noted that he had made Aramco “a leader in the global energy transition.” Yet Aramco has said it is boosting its production of oil and gas in the coming years. It has also pushed back on efforts by global organizations to reduce oil use, including at the 2022 United Nations global climate summit in Egypt.

Even as Fink’s rhetoric has shifted around the environment and other social issues, he has largely been steadfast in his support of and interest in Saudi Arabia. He typically visits the kingdom as often as three to four times a year, Fink said in a CNBC interview. He traveled there twice in the last 18 months but has yet to visit this year, a BlackRock spokesman said.

In June 2018, Fink co-hosted a multiday event with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman at his summer palace in Jiddah, where they invited roughly 150 global heads of states and heads of major financial firms.

Months later, in October 2018, Crown Prince Mohammed ordered the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Fink, like most other chief executives and heads of state, declined to attend a global investment conference scheduled for a week after Khashoggi’s death, though Fink personally intervened to see if the kingdom would delay the conference. They wouldn’t.

While Fink called Khashoggi’s murder “horrifying,” he also said that he wouldn’t “run away” from doing business with Saudi Arabia.

In April 2019, when Aramco tapped the international markets for the first time with a $12 billion debt deal, BlackRock was among the largest subscribers.

Fink also personally sought to lure Saudi Arabia’s sovereign fund and other Middle Eastern state-owned funds to buy BlackRock shares.

When BlackRock’s largest shareholder, PNC Financial Services in Pittsburgh, wanted to sell its roughly 22% stake in the firm in early 2020, Fink told the chief executive of PNC, William Demchak, that he wanted to help choose the new shareholders, according to people with knowledge of the deal. Although Fink’s interest was understandable given the huge portion of BlackRock’s shares, bankers and other advisers were surprised at his level of involvement in the deal.

Fink personally called the heads of many Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds, including Saudi Arabia’s PIF, the people said, and quickly brought them on as investors in a roughly $13 billion stock sale.

Fink continues to integrate BlackRock into Aramco’s work and Saudi Arabia’s finances. Saudi Arabia hired BlackRock to advise the kingdom on its newly created $50 billion fund dedicated to projects that upgrade its domestic infrastructure. In December 2021, BlackRock led an investor consortium that spent $15.5 billion to buy a 49% stake in Aramco’s natural-gas pipeline.

Nasser, who will fill a board seat vacated by Bader M. Alsaad, a former director of Kuwait’s sovereign wealth fund, hasn’t wasted time getting to work. In mid-July, shortly after his appointment, the Saudi Arabian executive traveled to France and Germany to attend board meetings, where the directors also met BlackRock clients.

c.2023 The New York Times Company. This article originally appeared in The New York Times.