The Conference Board foresees a “short and shallow” recession soon, driven in large part by the war in Ukraine and consumer reaction to inflation.

A debt-ceiling showdown in Congress could affect how short and how shallow, chief economist Dana Peterson said when she spoke in February on a Conference Board panel.

This recession wouldn’t look like past recessions, though.

“If we are going to have a recession, it’s probably starting right about now, February or March, or as late as the beginning of the second quarter,” Peterson said.

GDP isn’t expected to nosedive, because businesses, government and consumers continue to invest and spend, she said. It grew 2.9% in the most recent quarter, even as other leading indicators signal a recession.

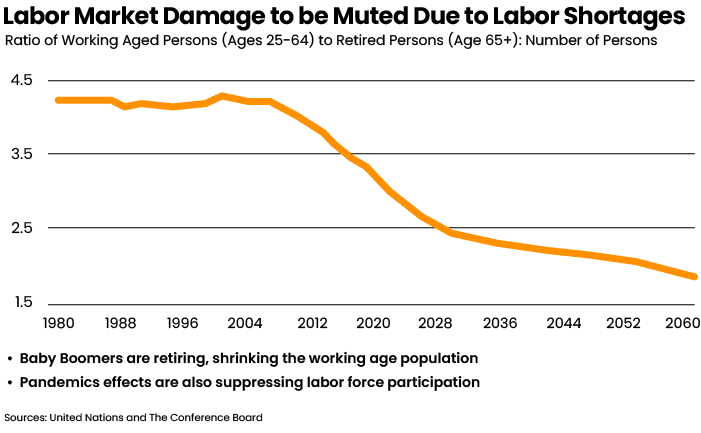

Also unlike past recessions featuring job shortages, this one would feature labor shortages as baby boomers retire yet drive demand for goods and services, she said.

“Even though we anticipate a short and shallow recession in the U.S., we don’t anticipate material deterioration in the labor market,” Peterson said, pointing to a worst-case unemployment rising short-term to 4.5%, about 900,000 jobs. The current 3.4% unemployment is a 54-year low that’s expected to continue to drop.

Housing costs, a primary driver of inflation, reflect now what was happening a year ago, she said. Home-price deceleration that’s “in the pipeline” will trickle to other goods and services.

“We don’t expect the Fed to blink,” Peterson said of its raising interest rates to fight inflation until it reaches 5% to 5.25%. “We don’t expect it to consider interest rate cuts until next year.”

The Fed will be highly focused on inflation until it settles into a 2% annual inflation zone, a target that could be hit by the end of next year, Peterson said.

Inflation’s inequity

As jobs, wages and spending all continue to rise, a recession’s inflation factor may not seem like a big deal for some consumers.

But Peterson said excessive inflation is a problem because it hits hardest on the lower end of the economic spectrum, crippling the people who need stability the most to survive.

Among the riskier pieces of the inflation puzzle is the “sticky” food prices, Peterson said. Grocery and energy prices are affected by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, known as the global “breadbasket,” because of the war’s disruption of food supplies on the international market.

The quality of job openings is another factor with inequities.

“Most of the job openings are in the industries where you have to physically show up for work,” Peterson said, such as those in healthcare and serving customers in restaurants, hotels and travel. “Some call it white-collar vs. blue-collar, but I prefer to think of it as whether you have to show up to work or not.”

In contrast, layoffs have been mostly in the more remote-work tech sector, which is adjusting its oversupply from the Covid-19 pandemic, when households equipped for at-home work and school, she said.

Despite wage increases, paychecks aren’t big in some of those jobs, she said. There’s imbalance in the winners and losers in whether wages keep up with inflation.

“Wages have been rising for quite a while now, but inflation is rising faster,” said Erik Lundh, the board’s principal economist for the U.S.

That complicates the Fed’s effort to bring down post-pandemic inflation, Peterson said. It’s trying to find the right balance to resist both supply-side factors and wage factors.

“Our consumer confidence data gauges different income groups, and it has been evident that the folks on the lower end of the spectrum are the ones who are less confident, which makes absolute sense, because when you think about the prices that have been rising, it’s food, gasoline and rent/places to live,” Peterson said.

Yet, workers in medical and hospitality sectors, for example, may not even notice a recession, she said.

It’s workers in higher-end jobs, like those in the contracting tech and financial sectors, who are more likely to experience “their own personal recession,” vulnerable to being among those 900,000 to lose their jobs, Peterson said.

“I would not want to be in that number, but it’s still really mild compared to what we’ve seen in prior recessions, where we’ve seen 5, 6 or 7%” of total workforce, she said. In the Great Recession, by late 2009, employment fell by 8.6 million, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“At least so far, it doesn’t seem like people are nervous enough about potentially losing their jobs to stop spending on goods and services,” Peterson said.

Soft landing

How much consumers are willing to spend will be key to how hard and how long a recession could be, Peterson said.

“Consumers are still very much focused on consuming goods and services, especially experiential services, and that’s contributing to higher inflation,” Peterson said.

The recent pop in retail sales may have been driven by January’s good weather, but she’s also watching how consumers are using their credit cards.

“We’ve seen credit card use expand in recent months, but we’ve also seen defaults and delinquencies creep up, so maybe we’re approaching the point where consumers are tapped out,” Peterson said.

The media affects consumer psychology and confidence too: People hear that others are getting laid off and might cut down their spending, she said.

But a recession is not about any one thing. “Recession in the U.S. is defined in a very complex manner” to mark when domestic production and spending has pulled back, Peterson said. “It’s not just one thing. It’s many things all at once.”

That’s why a recession could happen even amid robust hiring.

“This recession is different from other ones,” Peterson said. “It has never been the case that we’ve had millions of people exiting the labor market at the same time. Who are those people? It’s the baby boomers. They’re getting older, retiring and leaving.

“You don’t have enough younger people to replace them, and oh, by the way, our immigration policies are tight, so you can’t draw on that labor from abroad to make up for the baby boomers who are leaving,” she said. “And, oh yes, the pandemic has kept many people out of the labor market because it’s very difficult to return without child care. Same with elder care.

“It’s a mixed bag that we knew was coming,” she added. “That’s the demographic reality, and now it’s hitting us.”

Political disruption

It’s not new for a split-party Congress to use the necessary debt-ceiling adjustment as a political football.

A debt-ceiling debate is even riskier this year as that U.S. demographics stew is plated with the worldwide stress of post-pandemic supply challenges and its frenzied consumption – amid a draining war.

Lori Esposito Murray, who heads the board’s public policy center, said the U.S. needs to get its fiscal house to have a productive and prosperous economy in which all Americans can share. “It’s about time we solve the astronomical amounts of debt we’re accumulating. We’ve seen these crises: It’s the Great Recession. It’s Covid. It’s the war in Ukraine. That’s what’s fueling inflation … and affecting growth” Murray said. “We have to be anticipating the next crisis.”

Murray pointed to the lesson learned in 2011, when the debt-ceiling debate itself caused a downgrading of the U.S. credit rating.

“The downgrading didn’t happen because we went off that cliff but because we talked about it, which had ripple effects throughout the economy,” Murray said.

An actual default would have been much worse, of course, she said, but the lesson learned is “cataclysmic ramifications” to GDP if this conflict drags on for the next three or four months.

“It’s very easy to have the crisis and hit that cliff. but it’s much harder to recover from it,” Murray warned.

She said the Board would like Congress to form a commission that would take the debt ceiling off the table, so it couldn’t be used as leverage in political agendas.

The debt ceiling “is not the place to have the debate about spending and tax increases. It’s the place where we pay our bills,” she said.

Murray said she’s watching the momentum for a resolution of disapproval, whereby a president suspends the debt ceiling and Congress takes a vote, needing two-thirds of both houses to override it to put the debate back in the House.

“That seems to be picking up steam,” Murray said of the idea that Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., had considered in 2011.

The Conference Board has a hub, “Navigating the Economic Storm,” dedicated to current recession insights.

Linda Hildebrand is a longtime newspaper editor and consumer reporter.