In the NFL, Tom Brady is a very old man.

When he took the field on a recent Sunday night — with his Tampa Bay Buccaneers still hoping to make the postseason — he was 45.3 years old, 6 years older than the next-oldest starter in the NFL and the oldest starting quarterback in the league for the seventh season in a row.

In a league where most quarterbacks last about four seasons, Brady is in his 23rd. It is safe to call him the top 1% in terms of age, or even the top 0.1%. He is, himself, the end of the distribution.

There are many ways to contemplate Brady’s age, but the best one may be to look outside the sports arena, comparing him with aging workers still going strong in other professions.

Starting at quarterback at 45 is akin to being a family doctor well into his ninth decade. It’s like being an emergency medical technician — a job that requires running up stairs and lifting bodies on stretchers — at age 70. Or an artist in her 90s, a logger in his 80s or a biologist in her 70s.

We know this because the Census Bureau keeps records of the age distribution of nearly every occupation under the sun. Using this information, we set out to find a group of American workers who occupy the same part of the age distribution in their professions as Brady does in his.

We found nine such people from around the United States, and we asked them why, like Brady, they can’t seem to quit.

Of course, there is no such thing as a Super Bowl of baking, or an All-Pro team of the country’s logging foremen. There is no Most Valuable Bean Biologist award, although perhaps there should be. We do not claim that these workers are the greatest of all time at what they do. On the other hand, having talked extensively with them, we cannot rule it out.

Meet them, and decide for yourself:

The Tom Brady of Paramedics

Jesse Izaguirre, 70, Gardena, California

Jesse Izaguirre is a reformed ambulance chaser.

In the 1970s, he made $5 a pop following ambulances and selling pictures of accident scenes to a local paper in California’s Central Valley. One day, the ambulance company called him up — and offered him a job. In more than four decades since, he’s done everything: put in IVs, intubated patients, and even delivered babies (10 total).

These days, he works two 24-hour shifts each week transporting patients in Los Angeles. He bounces in and out of the ambulance. By his account, which The New York Times could not independently verify, nurses guess he’s in his 50s. All the slowing down he’ll admit to is that he loves to nap on shift.

“Some people ask, ‘When are you going to retire?’” he said. “I say, ‘First of all, it’s none of your darn business.’” He laughed. “I’m kidding. I’ll tell them anything. When am I going to retire? Hopefully never.”

The Tom Brady of Bakers

Helen Fletcher, 83, Clayton, Missouri

Helen Fletcher got her dream job in her 70s: in-house pastry chef for Tony’s, an upscale Italian restaurant in the St. Louis area. Now 83, she rises before dawn to make cheesecakes, tarts, biscotti, tiramisu.

“My mother died from complications of Alzheimer’s, and my brother was just diagnosed with it,” Fletcher said. “It’s extremely important for me to keep my mind and my body going.”

Before Tony’s, she ran her own wholesale bakery, which she opened in middle age. When not baking, she writes prolifically — filling cookbook after cookbook — and she’s a popular guest on local television, with thick white hair and a camera-ready smirk.

Behind the scenes, it’s messier. Professional baking is an exacting job, she says. Consistency is paramount. There’s no wiggle room. And there’s the occasional cake implosion.

“You always have disasters,” she said. “Anyone who’s been in the business for this many years and says they’ve never had a disaster? Chalk it up to a great big fib.”

The Tom Brady of Artists

Lilian Thomas Burwell, 95, Highland Beach, Maryland

Lilian Thomas Burwell recently had an exhibition in New York that drew so much attention, as she puts it, that she’s been making “real money.”

“I can’t keep up with myself anymore!” she said.

At 95, that’s how so many things in her life feel, including her art: still new, after all this time.

“It’s like it comes through me,” she said. “Not from me.”

She knew as a child in New York City during the Great Depression that she had to follow her instinct to create art.

Her parents thought she had lost her mind.

“They said, ‘You can’t make a living like that!’ Especially because of the racial prejudice,” she recalled.

“And I said, ‘But that hasn’t anything to do with it.’”

They compromised. She became an art teacher, then a teacher of art teachers. Each day, she hurried home from work to make her own art, which has since been exhibited from Baltimore to Italy. If creating was magical, teaching might’ve been even more delightful: It was like “throwing a pebble in the water,” with the result — her students’ lives — out of her control.

When she was featured in a recent documentary, former students, many of them now grandparents, wrote to her. They told her she was a big reason their lives had turned out one way or another — the pebble’s ripples, all those years later, finally visible.

“I said to myself, ‘I’m really somebody.’ Not because of who I am. But because of who I made.”

The Tom Brady of Composers

Deon Nielsen Price, 88, Arroyo Grande, California

As a teenager, Deon Nielsen Price admits, she had two loves.

“One was music,” she said. “The other was boys.”

She was singing at age 2, and through adolescence she dreamed of becoming a professional pianist. But she also wanted to marry and raise a family. Her mother assured her she could do both — and she did.

She brought up five children in a house full of music, while earning a doctoral degree. When one son became a clarinetist, the two formed a duo that performed around the world.

Today she writes music for ensembles across the country. “I’m just busy, busy, busy,” she said one day this fall while waiting for a plane. She had just wrapped up a recording session and was trying to fix a minor error in a composition for a concert a few days later, while juggling an influx of orders for a book on piano accompaniment that she self-publishes. And if that weren’t enough, there were dozens of grandchildren and great-grandchildren to visit.

“When I started out, when I was young, I always wanted to have a rich life,” she said. “And brother, have I.”

The Tom Brady of Tour Guides

Harvey Davidson, 84, New York

From a double-decker tour bus riding his typical route through the clamor of Manhattan, Harvey Davidson likes to point to a sign that reads: “Unnecessary noise prohibited.” The tourists love that, he says. “What is necessary noise?” he asks them, over the honks.

“People who are seeing New York City for the first time, they’re constantly looking up,” he said. “I have to get them to look down. To see things.”

Davidson only became a tour guide in his 60s, but he has a lifetime’s worth of New York City to share. Between stops he charms his charges with stories. He tells them about his messenger job for law firms when he was a teenager from Brooklyn, his encounter with Paul McCartney at the Empire State Building, and the time he was accidentally seated in a box beside Tom Hanks at a performance of “Chicago.”

“People saw me with him, and so they were handing me their programs to sign,” he recalled. “I should’ve signed them.”

The Tom Brady of Biologists

Maria Elena Zavala, 72, Los Angeles

Maria Elena Zavala is trying to make better beans.

She’s a professor of biology at California State University, Northridge, where she studies root systems and the nutritional content of beans.

“I’m curious about how these plants work,” she said. “Still. After all these years!”

But it’s the students, not the plants, who keep her up at night — and keep her working. She teaches a disproportionately poor, unprepared population. Many are Hispanic and first-generation students. The majority have Pell Grants.

She’s taught them how to read critically, helped them get practical job skills, and, perhaps most important, shepherded dozens into doctoral programs. A historian once told her she was likely the first Mexican American woman to earn a doctorate in botany in the U.S., and she doesn’t want to be the last.

“I want everybody to see the beauty in science and participate in science and contribute to science,” she said. “It’s important for everybody. People’s curiosity didn’t get left at the Rio Grande. It didn’t vanish when they crossed the border.”

The Tom Brady of Loggers

Earl Pollock, 82, Hamburg, Arkansas

Earl Pollock is no fan of weekends.

“I can’t wait from the weekend till Monday morning,” he said.

Monday morning usually finds Pollock, a logging foreman, in the cab of his bulldozer, flattening a road through the timber woods. It’s a natural evolution from the job he had as a teenager decades ago: felling trees with a power saw.

“Everything is mechanical work with air conditioners and heaters; nobody’s out in the heat or cold anymore,” he said. “It’s not like it used to be.”

All these years in, the job still tickles him. From the cab, he spots meandering black bears and the big deer that he likes to hunt in his free time. Sometimes he catches disasters waiting to happen — like an old tire in the path of a machine, prone to start a fire. And he’s never once been injured.

“I keep the job on my mind 24/7,” he said. “I guess I’ll stay till I can’t get up in the morning.”

The Tom Brady of Dancers

Dianne McIntyre, 76, Cleveland

Dianne McIntyre is now part of the history she has always loved.

In addition to her work in choreography and dance — more than five decades of it — she has been an avid student of dance and African American history. Now when graduate students write papers on the history of dance, they call her up to ask about her life.

“Longevity is really a gift,” she said.

She still dances, too. Not the kind of dancing she did in her 20s, she says, but new movements. “You learn to choreograph for yourself, to have an expression that can still be uplifting.”

Recently she performed in New York City, the same place where she once began her career and started her dance company — young, eager, buoyed by the free jazz movement and the city itself, but uncertain of whether she could make a living out of dance. Now she knows that it worked out just fine.

“The only way I would stop any part of this — the mentoring, teaching, choreographing, all of that — would have to be an inner shift,” she said. “Something inside of me that would say, ‘Oh, I’m satisfied.’”

If that happens, she says, she might spend a bit more time at the spa. But for now: There’s still work to do.

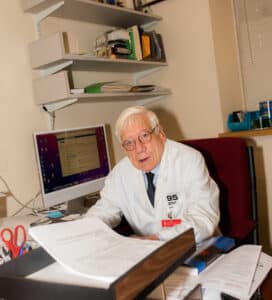

The Tom Brady of Doctors

Louis Caplan, 85, Boston

These days, Louis Caplan, a practicing neurologist and professor of medicine, is teaching students 60 years younger than him his favorite part of medicine: how to take a patient’s history.

“The thing I like best in the world is sitting down with a patient, getting to know them, trying to help them,” he said. “I’ve been doing it so long it’s second nature.”

The brain has revealed itself to him over decades. When he was in college, it was a vast, unknown space, he says: There was little doctors could see, and few ways to help stroke patients, the specialty he chose.

Caplan himself helped change that: He built the Harvard Cooperative Stroke Registry in the 1970s, an electronic collection of symptoms, risk factors, diagnoses and outcomes — at a time when computers were foreign to most doctors. And he wrote and edited dozens of books.

These days, when not teaching or writing, he still sees patients, many older themselves. “My own physician told me that you go to the emergency room, and the doctors are just children!” he said. “Older patients, they’d prefer to see someone with a little gray hair than someone they think is too young.”

—

Methodology

The distribution for other professions comes from American Community Survey five-year microdata from 2015-19, provided through IPUMS USA at the University of Minnesota. For each combination of gender and profession, based on 2010 occupational descriptions, respondents were counted only if they were currently employed.

c.2022 The New York Times Company. This article originally appeared in The New York Times.