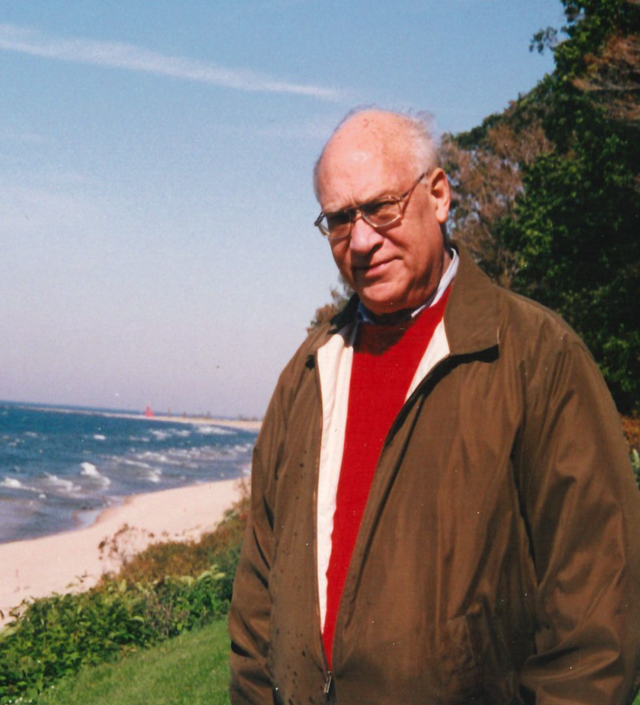

Much has been written in recent years about the graying of the financial services industry, where the average advisor is now about 55. But Richard “Dick” Wendin, 82, who landed his first job in the industry in 1965 and still goes to the office a few days a week, might be more likely to call them kids.

I first spoke with Wendin, an investment advisor with Bloomfield Hills, Mich.-based Heber Fuger Wendin (HFW), nearly a half dozen years ago when I wrote a profile piece on the fee-only financial advisor and investment counsel firm.

When I recently told him about Rethinking65 and its focus on planning for the second half of life, the first thing he said to me, with a chuckle, was, “Are you going to ask me why I’m so stupid for still working?”

Had he thought at all about retiring when he reached his late 50s or 60s? “Not really. The further away you are from retirement age, the more you desire it,” he told me. “As you get closer, you realize retirement’s not such a great thing for most people.”

“The further away you are from retirement age, the more you desire it. As you get closer, you realize retirement’s not such a great thing for most people.”

Wendin — a 6-foot 3-inch U.S. Army veteran who walks with a red, white and blue cane — had planned to be in office during our phone interview but decided to work from home that day because it was snowing. He usually arrives at the office by 6:30 or 7:00 a.m. and leaves by 11:30 a.m. or noon, he said, because it enables him to drive the 27-miles between his home and office when the roads aren’t crowded.

As soon as he arrives at work, he turns on Bloomberg and sends emails to one of his clients, a retired bank president, to share news about his client’s portfolio companies. “He’s the younger brother I never had,” he said. “We’ve become very good friends.”

Wendin’s other long-time client is the endowment of a small community hospital. He communicates with the hospital’s treasurer, who has the authority to approve endowment investments. The treasurer, who is mostly interested in discussing asset allocations, is busy with his main job, said Wendin, so when they speak it’s at 7:30 a.m.

The endowment “happened out of nowhere,” said Wendin, when, about 20 years ago, a woman in the community died and left the hospital $3 million to establish an endowment. “Everybody thought she was just a little old lady living in her house,” he said. “Nobody knew she was worth a penny. The endowment is now worth about $17 million, he said.

Wendin’s life and career are very much intertwined. His father, Sigurd R. Wendin, co-founded HFW in 1934, five years before he was born. As a child, he visited the office and played with the Dictaphones.

“My dad worked till he was 86,” he said. “I hope to get at least that far, and hopefully better than that.”

Wendin’s older brother, who lives in Connecticut, worked as a broker until he was 75 and spent decades on the New York Stock Exchange. “His feet just gave out after being on them for 30 or 40 years,” he said. “Longevity runs in the family a bit, at least among the male members.” He mentioned his sister is deceased.

After graduating from Yale, Wendin served several years in counterintelligence in the army. Shortly after taking a discharge, he joined Detroit Bank & Trust Company (now Comerica), at 26, and worked in the trust investment department where he served personal and institutional accounts.

“I was supposed to cover 300 to 400 accounts — and that was just ridiculous,” he said, so he kept the big accounts in his desk drawer. But “there was one very nice older guy, and every year at Christmastime he’d come in and put a bottle of scotch on my desk,” he said, “so I put his account with the other big ones.”

After five years at the bank, Wendin moved to Donovan Associates, a Detroit-based land investment firm where he was responsible for investment capital procurement and investor relations. The real estate work disappeared in the 1970s when the first oil embargo hit, he said, so he joined his father’s valuation company, Sigurd R. Wendin & Associates, which shared an office with HFW.

Wendin’s father and his partners, Ted Fuger and John Heber, originally agreed they would not hire any of their sons “because they didn’t want any nepotism,” says Wendin. But “when HFW had several guys leave in ’82, it just so happened that the people who were left were all bond guys,” said Wendin, who had stock experience. The firm brought him in for 90 days—and never replaced him. And so he became an investment advisor and portfolio manager for personal and institutional equity and balanced accounts.

Wendin likes the atmosphere at HFW, where a team of 10 manages more than $4 billion in assets. “There’s definitely a difference between guys that are comfortable working in big corporations,” he said, “and guys like me who would much rather be in a small company, knowing everybody.” He also thinks a big corporation would’ve had him walk.

“They don’t tend to keep you around past retirement age,” he said, “and they may very well offer you early retirement.” But the HFW family is different.

“Dick is pulling his weight at Heber, just like all of our other investment advisor reps,” said Dave Barnes, president and CEO of HFW, who has worked with him for decades. “Also, since working a few times a week requires him to think, stay on top of the markets and exercise his investment advisory judgment—and his legs, at least a little—I suspect this helps keep him mentally sharp.”

“His expertise is invaluable to us,” added Barnes, “so it’s a two-way street.”

Wendin started cutting back from full time to part time around 2006. He cut back his client load gradually, and most of it happened organically as clients died, sold their businesses or moved away. He didn’t stop taking on new clients; he just stopped actively seeking new clients in his 70s. Becky Gersonde, a vice president and investment advisor at HWF, also began working with Wendin on some of his clients. Wendin now has two clients who are his main focus.

“Dick brings a refreshing, humorous perspective to the office with his stories and dry sense of humor,” said Gersonde. “In addition, Dick’s first-hand knowledge of Heber’s past and the investment markets gives us valuable historical perspective.”

“Dick reinforces the importance of establishing and maintaining not just professional, but personal relationships with clients based on his countless stories of success and occasional failures,” she said.

Wendin has had to adjust to new rules and regulations, and technology. Heidi Barnes, HFW’s treasurer and systems administrator (and Dave’s wife), shows him what’s wrong when he has technical difficulties, said Wendin, noting her office is next to his. He also continues to do stock and bond trades by phone. “I still like to hear a human voice and establish relationships,” he said.

Wendin encourages advisors to tell their older clients to never make a decision without first speaking to someone who is an expert in that field. “If somebody wants you to sign something, get an attorney to look at it first,” he said. People have solicited his wealthy retired client to invest in their ventures, and he has cautioned him against this.

Wendin bristles when he hears the term “getting one’s affairs in order,” he said, “because it sounds like you’re ready to die,” However, “we need to devote time to find the right people to do the right thing at the right time,” he says. “If I can’t help somebody, I want to point them in the right direction.” He also stressed the importance of helping both spouses understand their finances.

When he began to work in the trust investment department at Detroit Bank & Trust, “it was just shocking for me to learn how many auto executives in Detroit had told their wives absolutely nothing about finances, and how rich they were, and that sort of thing,” he said. The widow of a senior vice president at Ford wanted to take a trip to Europe with her friends and didn’t know if she could afford it. Wendin assured her that she could. Although that was more than 50 years ago, many spouses are still unaware of their finances.

Staying Active

“One of the problems in retirement is, what do you do?” said Wendin. His brother and his nieces and nephews are scattered across the country and the world, “so I don’t have family things to distract me,” he said, “and I don’t have any hobbies.”

“I had to get rid of my boat because I was getting so old I couldn’t move around on it,” he said, “and it was fairly big so I couldn’t run it by myself.” It was an Egg Harbor 43 wooden boat from around 1970, said Wendin, who learned to sail at the Detroit Boat Club. In his younger years, he also rode horses and his motorcycle.

Wendin is the commander of his American Legion post, which raises money for veterans’ causes, including vets returning home who are having difficulty adjusting to civilian life. “The ones who need it, we help; the ones that don’t need it, we try to get money out of,” he said. The pandemic has put an end to the monthly dinners, and when he socializes with friends, they sit on opposite sides of the room. Still, Wendin feels pretty lucky.

He doesn’t take any medication, which his doctor has told him is pretty amazing. “I should do more exercise than I do,” he said. “One friend of mine walks five miles a day, but I’m not going to do that.”

Jerilyn Klein is editorial director of Rethinking65. Rethinking65 is doing a series of articles profiling advisors who’ve worked long past traditional retirement age. If you are interested in contributing, please contact her.