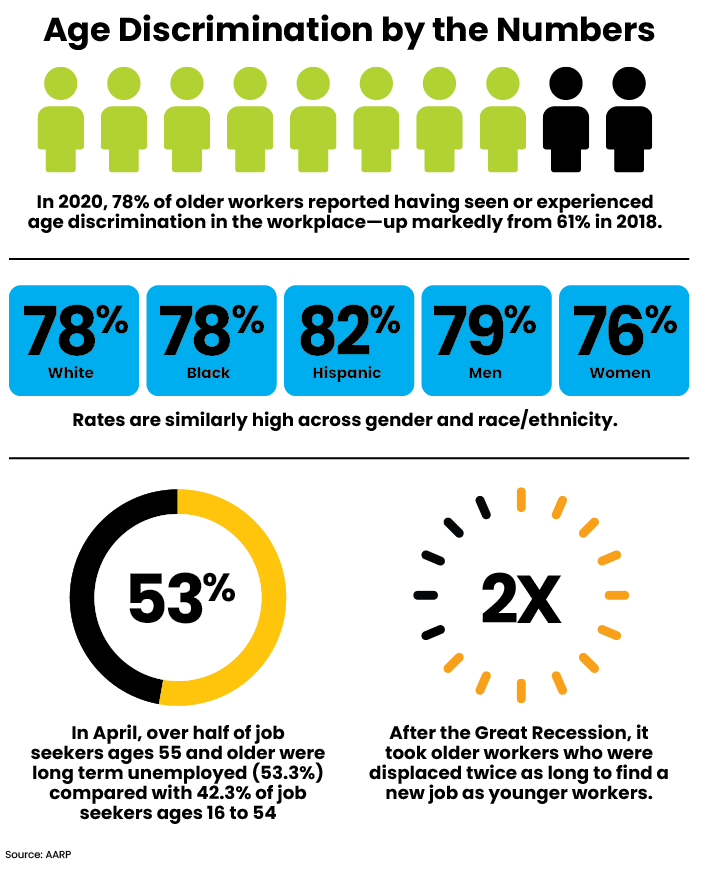

Older job seekers hoping for a welcome mat in this record-high jobs market are encountering more age barriers instead, according to an AARP Foundation survey.

So are those who have jobs and now have to work past age 65, because Social Security stretched the number of years the last baby boomers and beyond must work before collecting on their federal insurance policy.

Age discrimination is at its highest since AARP began collecting the data about a decade ago, AARP says.

Almost 80% of workers 55+ say they have seen or experienced age bias first-hand on the job.

And 2 out of 3 women age 50 and older say they are regularly discriminated against, both in and out of their workplace.

Too-cool-for-school wordplay and court rulings that snatched anti-bias protections from job seekers keep AARP Foundation attorney William “Bill” Rivera on the lookout for lawsuits.

“There are so many different places where employees can be affected by things employers do or want to do” to weed out older applicants and get rid of longtime workers, Rivera says.

“We need to be very vigilant to ensure the older workers are on the same level playing field as younger workers,” he says.

Proving bias in court

Rivera doesn’t sugar-coat the legal landscape.

“These are long fights,” says the senior vice president for AARP Foundation Litigation. “They’re hard to prove. Most people who lose a job need a job — and focus their energies on their next jobs.”

AARP doesn’t seek to advocate for individuals. It takes on age-discrimination lawsuits and legislative efforts that would broadly improve conditions for older workers across America.

“We bring cases that raise common issues that we feel go beyond the individual workers who are affected,” Rivera says. “We care about all those individual cases, but age discrimination happens with such frequency” that AARP narrows its efforts to cases with sizeable numbers of individuals as a class and cases that tackle an issue that can make an objective impact for everyone down the road.

Private attorneys will bring cases for individuals, “but they take a lot of time and are taxing for those individuals,” Rivera says.

Case in point

“Some are subtle barriers to entry that we’d like to establish better in law,” Rivera says.

After years of Equal Employment Opportunity Commission advice that the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 protects job applicants against discrimination both direct and indirect, some federal district courts have ruled otherwise since 2016.

One case Rivera has been chipping away at for years is Raymond v. Spirit AeroSystems.

In 2016, 24 longtime engineers sued Spirit, which eliminated their jobs in a reduction in force, then advertised their job descriptions and hired young workers, according to their lawsuit.

The engineers say the Kansas company violated the ADEA of 1967 when it wouldn’t rehire the engineers. They also say the RIF was tainted by subjective performance reviews that used vague criteria, such as “versatility” and “criticality,” that set up older workers to be singled out on criteria not used for all others.

AARP Foundation also litigated Kleber v. CareFusion. Dale E. Kleber was a 58-year-old attorney who applied for an in-house counsel position advertised for applicants with “3 to 7 years (no more than 7 years) of relevant legal experience.” CareFusion hired a 29-year-old.

The ADEA explicitly prohibits job advertisements from “indicating any preference, limitation, specification, or discrimination, based on age.”

Kleber argued that limiting applicants to no more than seven years of work experience was illegal bias, because the ad’s intent is the age disparity the ADEA prohibits.

The distinction is the word “age,” Rivera says.

In both cases, the courts ruled the ADEA didn’t protect the worker because they were job applicants and not employees.

“You don’t even get to the question of whether (the employer) is discriminatory,” Rivera says.

Taking it to The Hill

“We think it’s not what Congress intended,” Rivera says.

“This is where lawyers start counting angels (dancing) on the head of a pin,” he says, referencing a metaphor for wasteful effort arguing minutia of a problem while overlooking a solution.

So, he and other advocates are working Capitol Hill for ADEA amendments to make it clear that the landmark anti-age-discrimination legislation, like Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, allows job applicants to sue for age discrimination.

It’s not the only hole — that courts have carved in long-accepted understanding of anti-discrimination law that AARP lobbyists are tackling, too.

Since 2009, some courts have required age bias to be the sole motive for discrimination, based on the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Gross v. FBL Financial Services.

Legislation progressing in Congress would explicitly put the ADEA of 1967 on equal footing with Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

The U.S. House in June 2021 passed H.R. 2062, Protecting Older Workers Against Discrimination, in a 247-178 vote, with 29 Republicans joining all 218 Democrats voting. The identical S880 has not been taken up in the 50-50 Senate, where the bill is subject to filibuster; at least 60 senators are needed to let the bill come to the floor for a vote.

Some successes

Some of AARP’s legal fights have changed law, Rivera says. One was the requirement that employers conducting a RIF provide workers they lay off with a list of ages in eliminated positions.

Some cases settle favorably out of court, so they don’t establish case law.

In 2018, Ohio State University settled its infamous “grim reaper” discrimination case. Fired older women in good standing showed internal memos referring to them as “dead wood” and “millstones” around the administrator’s neck.

“We were able to obtain a favorable settlement and get them back into their positions, as well as a recovery (of back salary) and attorney’s fees for them, which was great,” Rivera says, but settlements don’t fix laws and legal interpretations that allow agism continue.

The OSU settlement didn’t prevent a lawsuit filed earlier this year alleging internal communications show IBM terminated older workers who executives called “dinobabies” they planned to make “extinct” and vowing they “must change” their “dated maternal workforce.” IBM denies it “engaged in systemic age discrimination,” according to published reports about Lohnn v. IBM in the southern New York federal district court.

New tech, new barriers

“One thing we’ve been looking at is the use of AI, artificial intelligence, in the applicant screening,” Rivera says. “Many times, no human is looking at the resume.”

That makes it even harder to prove age discrimination took place in the hiring process, he says.

Automated screening “is a black box, difficult to see through. Decisions are difficult to trace to one person or even the employer. It adds to the challenge that so many people face when they’re looking for a job,” he says.

If a 50-plus worker gets past those this screening and faces real people in an interview, age becomes more apparent.

If a 50-plus worker gets past those this screening and faces real people in an interview, age becomes more apparent.

“Make notes,” Rivera says.

More than 4 in 10 people in the AARP survey say they’ve been asked for age-related information on an application or in an interview in their efforts to get back to work.

Watch for curiosity about things that would indicate age, for example, “How do you feel about working for people younger than you?” or “How many years do you anticipate working before you retire?” Some interviewers might try to chat about a period in history that would reveal age.

“If any question made you feel uncomfortable, you want to keep (written contemporaneous) notes about that experience,” he says.

Help in the meantime

AARP is a baby boomer, itself, born in 1958 as the American Association of Retired Persons.

Among resources for members at its website are:

- Free resume review by a professional who highlights skills and gives personalized feedback.

- Quiz to test knowledge of how to “age-proof your resume” and tips to help do better.

- Job board that includes employers who pledge to AARP that they are committed to an age-diverse workforcewith search filters designed to narrow viable help-wanted ads.

- Strategy workshops in AARP’s Back to Work 50+ coaching program.

- Skills courses that qualify for college continuing-education credits, for example, the fundamentals of Microsoft Office software and techniques for working by remote. The partner firm discounts more intensive college-level coursework and certification programs.

- Small-business advice and information.

AARP’s survey, Understanding Older Workers During the Coronavirus Pandemic, included 1,322 respondents ages 40 to 65 either working or recently unemployed in December 2020.

Linda Hildebrand is a longtime newspaper editor and consumer reporter.